I was in Tucson a few weeks back for work and met up on 4th Avenue with a friend of mine. 4th Ave is Tucson’s little off-campus bar strip. It’s got head shops, some eateries, and plenty of bars. It’s a thing people in Tucson do, “Heading down to 4th.” It was middle of a weekday afternoon so most of the hustle and bustle there was either the hobos du jour or all the bars setting up for weekend graduation festivities. I had a beer.

The topic of the Raiders came up and I relayed to my friend (a big Raiders fan — maybe even bigger than RTD), as I did to all of you in weeks one and two, that the Alazona proposal would actually be a terrible opportunity for Tucson. I think my point was taken but, as we dove into the minutiae that is analyzing why a bad city is objectively bad, where the opportunity costs were misspent, and at what point a place of 500k (nearly a million including the surrounding areas) crossed the event horizon of suck where, short of a Bayside High School type oil discovery in the middle of Arizona Stadium, Tucson went from simply a dump to a census-designated version of the Yucca Mountain waste repository.

So this week I would like to give a little background — and don’t let me get all [DFO] History Corner about this — on how Tucson got to be where it is today. Specifically, a city that could feasibly host an NFL team for seven games but also is a place where such an agreement is wholly impossible to ever occur. So far, I assume all anyone knows about Tucson comes from it’s brief moments on the national stage.

Now, I’m not going to say Tucson is the absolute worst place but I thought about it when I read Balls’ piece on Los Angeles. One of the highlights of LA — a place that where I have absolutely no interest in living but absolutely concede is a Good City — is that it has everything. Any interest you got, they have an established and developed community that will foster growth in your interest. Tucson — and many other cities fit this bill — is simply not so easy in this regard. Tucson is a place that has serious income (and the associated income disparity) issues and, frankly, it all flows down from there. The power, the money, the civic decisions — there are very few voices at the table. Tucson’s proposed trajectory over the last two decades relative to what actually happened (a bastardized version of the big dreams promised) is so predictable it would give Hippo a sure-thing rager.

Tucson is one of those “It’s a big small town” places. And in 1999, a multi-million dollar special taxation district proposal was put on the ballot. At the time, Tucson’s downtown was struggling as residents were moving to the unincorporated county and suburban lands outside city limits. The proposal was to revitalize downtown Tucson and create a [insert generic urban development language — walkable, vibrant, art, restaurants, culture, work/live/play…] experience.

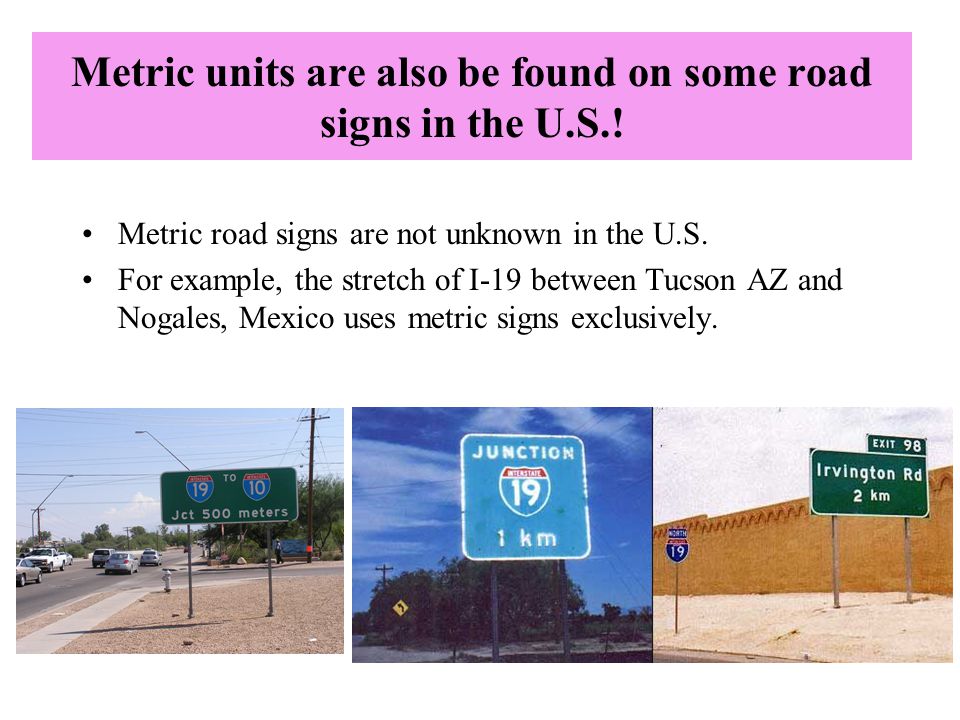

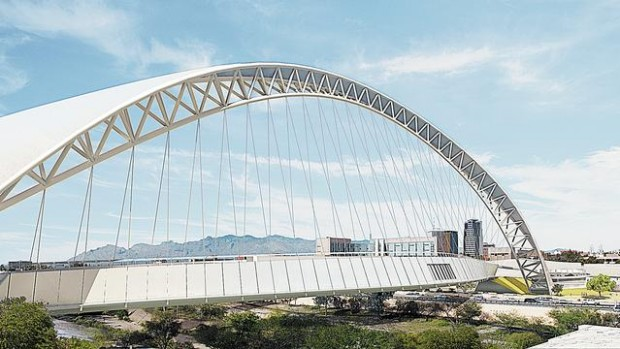

Highlights of the proposal included plans for a new arena, new science center, thousands of new hotel rooms, and a massive pedestrian bridge that would link the existing downtown footprint across the interstate to the land at the base of A-Mountain. The bridge would be an architectural feature that would define the Tucson landscape.

The proposition passed. It was actually one of the most successful propositions ever balloted, securing over 60% yes votes.

Now, if you visit downtown today, 20 years since the proposition was passed, it IS completely different than before. I mean, it was an absolute dump before — complete with vacant storefronts; undeveloped lots; and just a seedy ass transient population. Now it is a lot more yuppied up. The major projects were all dropped — no Rainbow Bridge, no aquarium, no science center, no new arena, no signature hotel/conference center — but there are plenty of hipster restaurants, hipster coffee shops, and ground-floor boutique retail. West of I-10 (which would have been connected by the Rainbow Bridge) has significant development and all this area, plus 4th Avenue, is linked to the university via the SunLink street car system.

But the eventual success (SPOILER: Success is an easier term to stomach if you do not consider the historic public expenditures of the Rio Nuevo) of downtown Tucson was more a result of the state takeover and correction of the district — and this is where we talk about Tucson, as a city without the proper competent leadership sitting down with the sharks that are NFL/Oakland Raiders non-Mark-Davis negotiators — after the city’s Rio Nuevo board $250 million in expenditures was audited in 2010. The results, which were part of an 18 month FBI investigation, concluded that tens of millions of dollars had been wasted but, since it was simply a matter of incompetence, the state attorney general declined bringing charges.

Now, if I may pierce the fourth wall for an aside here — I want to let you all know that I am being selective about the examples presented here. You go through audits of this much public money and you’re bound to find expenditures that are probably inappropriate but also small potatoes in the grand scheme of things — like how Rio Nuevo picked up $9,000 in security and barricades for two years of the All Souls Procession event. Opponents of Rio Nuevo scream about mismanaged funds but, honestly, who cares? I don’t. All Souls is downtown within Rio Nuevo’s geographic footprint and $4,500 a year for security just sounds like some horse trading with the city.

Conversely, you’re going to find line items that seem so shocking that your initial reaction is to assume that there is no way such negligence could be possible. For example, Rio Nuevo spent nearly $1.25 millions on public relations — outside of naming sponsorships and other consulting — during their dismal opening decade. Why? Because there was no progress to show and the board was under much public criticism. Using funds to cheerlead a project that is wasting (literally, paying consultants and then scrapping everything produced in those contracts) tens of millions of dollars a year actually epitomizes the Rio Nuevo board’s approach to management.

But most of what you see is arguably in-between and very much just waste. Millions of dollars in consultant fees on projects that never really had a chance and, not surprisingly, never neared construction — outcomes that any longtime resident of the city could have told the Rio Nuevo Board. An aquarium? Shut the fuck up, idiot. The Rainbow Bridge [To Nowhere] was never a feasible idea from the moment it was proposed and, to this day, those renderings remain the iconic image of Rio Nuevo’s broken promises.

So why was Rio Nuevo, prior to the state taking over, such an abject failure? Well, I agree that it basically boils down to the structure of the district (see below quote from board member Alberto Moore):

The fundamental flaw that doomed Rio Nuevo from the beginning was that the State gave the City of Tucson the authority to operate the District. The problem was made worse because the City of Tucson had a shaky accounting and recordkeeping system to begin with.

Because the Rio Nuevo District was so closely tied to the City of Tucson, the City often failed to treat it as the separate, independent body that it was and is. As will be illustrated, many of the problems and lawsuits today are a result of that blurring of the lines that occurred between the two entities.

In short: Tucson was way over their heads to take on such a project but the state let them do it anyways. And the state legislature — heavily republican and always critical of Tucson, a democrat pocket in the state — broadcast every failure along the way, until they finally stepped in and took control. We’ll go more into the political boobytraps at a later time.

So to close up this chapter introducing Rio Nuevo, I’d just like to remind the reader that this is all presented as substantive information when considering how big of a rube Tucson would be if they ever made the tragic decision to enter negotiations with a ruthless entity like an NFL franchise. Many towns and cities in America are terrible but they’re also fortunate enough to not think they’re something they are not. Tucson’s cross to bear is its own unfounded confidence that it can hang with the big dogs thanks to decades of being jobbed by Raytheon, IBM, and the University of Arizona who end every fleecing negotiation session by pickpocketing the city and then saying, “Man, you guys at the City of Tucson are pros. You sure stuck it to us. Congratulations on, yet again, perfecting the Art of the Deal.”

Next time maybe we’ll dig a further into the current characters who would be representing Tucson in any such Alazona negotiation and try to get some insight into just how they’d hold up against a party like the Location-Off Raiders.

[…] I’m driving back from Tucson today so let’s make this short and sweet. Submission here and your Week 12 Quotables results […]

[…] Rio Nuevo translates to New River and is the name of the downtown revitalization initiative introduced in Chapter 3. […]

[…] negative consequences to Tucson of actually pitching Alazona as a serious proposal; and, [CH 3] a brief example of the millions wasted the last time the brain trust of Tucson attempted to s… — has been backwards facing. “Sure”, some may argue, “Rio Nuevo took $400 […]

Oh so that’s why Kenny Lofton never moved back to Tucson?

I really am enjoying this. Great work Blax.

I want to say that I LOVE this series and can’t wait for the next installment.

Having experience with the city (visiting it often in my youth and having my parents living there for a few years later in life) makes me appreciate all this so much more.

Come on, instead of the LV Raiders, you could call them the Tuskan Raiders and have Disney design the Star Wars themed stadium and outfits (the landscape looks enough like Tatooine already), or even the Tuscan Raiders – with Italian themed pirates and sell lots of overpriced red wine!

“You can’t spell T-U-S-C-O-N without S-U-C-K!” – intellectually challenged Tucson residents.

Don’t forget ASU grads.

So, the City Council?