During the course of the year, I have taken to various Open Threads to teach about pivotal or interesting moments during the course of 1918, the final year of the war. The mutual goals were to keep you interested and provide reading entertainment on evenings when the sports calendar was a little light.

Below are the collected efforts of my history degree, on the Saturday before Remembrance / Armistice / Veterans Day. When you’re watching the games tomorrow, or at a ceremony like myself, I’ll be touched (non-Sandusky way) if something I wrote enters your brain when a commemoration is announced.

As always, thanks for reading.

January 8: the 100th anniversary of President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points“.

The US joined the war in April 1917, due to the “unrestrained, unprovoked aggression of the Imperial German government”, which was the German campaign of “unrestricted submarine warfare” they began in February 1917 in an attempt to starve Britain into surrender. [An published secondary reason was that the US needed to protect its investment if Britain and France lost, the US government would lose all the credit it had both extended and guaranteed to those two countries, resulting in a possible economic collapse from a war they never participated in.]

To sell the war to US voters, President Woodrow Wilson conceived his “Fourteen Points”. These points stated desired US outcomes in exchange for their participation in Europe’s war. They were needed as a ‘reason’ for why the “New World” had to go assist the “Old World”, to convince skeptical, isolationist US voters, to whom US politicians are beholden.

The 14 Points can be broken down into 4 components:

- how to prevent future wars → Sections 1-4

- dealing with Germany → Sections 6-8

- accommodating oppressed nationalities → Sections 9-13

- post-war war prevention and conflict resolution → Section 14

The document is consistent with US isolationist beliefs, because the proposed “League of Nations” (Section 14) and redesigned world would hopefully prevent the US from having to fight in future wars. It helped sell the people on the necessity for joining the war, and the brevity of time the US was involved prevented the rise of a large anti-participation movement.

Counter-argument: World War Two.

January 23: Negotiations between Russian Bolshevik Government and Central Powers suspended.

The Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917 installed Lenin and his followers in power over Russia. [For those who don’t know, the Bolshevik Revolution was actually the second revolution in Russia that year. The first occurred in March, overthrowing the Tsar but keeping Russia in the war.] Lenin and the communists came to power promising a swift end to the war, as part of his “peace, bread and land” pledge to gain popularity and cement the foundation of the Revolution.

The Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917 installed Lenin and his followers in power over Russia. [For those who don’t know, the Bolshevik Revolution was actually the second revolution in Russia that year. The first occurred in March, overthrowing the Tsar but keeping Russia in the war.] Lenin and the communists came to power promising a swift end to the war, as part of his “peace, bread and land” pledge to gain popularity and cement the foundation of the Revolution.

The Russians declared a ceasefire on December 22, 1917 and began peace negotiations with the Germans. But Russia had a poor bargaining position:

- Lenin wanted Russia out of the war, and

- Germany knew it

Germany, as a result, demanded huge territorial and financial concessions, primarily

Lenin didn’t care. His government entered negotiations on the premise that all losses would be returned after anticipated revolutions in Germany or the West. In fact, the Russian withdrawal from treaty negotiations on today’s date was done in anticipation of stretching out the negotiations in hopes there would be a revolution somewhere in the West that would avoid Russia having to lose territories. Commissar of War Leon Trotsky led the Russian negotiating team, and demanded peace without concessions, knowing the Germans would never agree to it. In Trotsky’s words: “To delay negotiations, there must be someone to do the delaying”.

That thinking had some resonance. There were agitators working to foment revolution in the West, primarily Germany. To aggravate the German negotiators, Trotsky would appear at negotiation meetings with Bolshevik propaganda written in German, supposedly “being distributed” on the streets of “Berlin”. These tactics would work until mid-February, when the Germans decided to resume actions in the East, to either force Russia to capitulate to their demands or achieve total victory over Russia itself.

This German offensive quickly reached the outskirts of the-then capital city of Petrograd (later Leningrad, now St. Petersburg), forcing the Bolsheviks to move their seat of government to Moscow. This was made worse by the fact that the Bolsheviks were having to devote large amounts of resources to fighting their enemies in the Russian Civil War – the “Whites” – a loose alliance of former Provisional government supporters, Royalists and anti-communists. In essence, the Bolsheviks were fighting a two-front war in a concentrated area, and they needed something to give. The Russians hurriedly resumed negotiations, leading to the disastrous Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, a treaty that would ultimately have implications impacting the rise of Hitler and the outbreak of World War Two.

One unintended effect of the Bolshevik’s delaying tactics was that it allowed the US time to become fully involved in the European theatre, despite having only joined the war in April 1917 in a primarily naval effort. Their army & armoured support on the Western front offset the German advantage to no longer fighting on two fronts. This allowed the Western allies the ability to push the Germans during the summer of 1918 into recognizing that defeat was inevitable, ultimately forcing German surrender in November 1918.

March 1: Treaty of Peace and Amity signed between the Finnish Social Republic of Workmen and the Russian Federal Soviet Republic.

On its own, it’s a fairly insignificant treaty to the overall concept of World War One. But it had enormous implications on the settlement of the eastern front and the upcoming & ongoing Russian Civil War. Plus, it had implications for World War II as well.

Prior to World War One, Finland had been a part of the Tsarist Russian Empire, known as the Grand Duchy of Finland. The ascension of Nicholas II in 1894 led to a climax in attempts at the Russification of Finland – elimination of the state parliament; Russian as the administrative language; mandatory conscription into the Russian army. After the Governor-general was assassinated in 1904, Russian defeat in the 1905 Russo-Japanese war led Nicholas to impose direct monarchist rule over Finland. The reign of Nicholas II prior to February 1917 is known in Finnish history as “The Second Period of Russification”.

Prior to World War One, Finland had been a part of the Tsarist Russian Empire, known as the Grand Duchy of Finland. The ascension of Nicholas II in 1894 led to a climax in attempts at the Russification of Finland – elimination of the state parliament; Russian as the administrative language; mandatory conscription into the Russian army. After the Governor-general was assassinated in 1904, Russian defeat in the 1905 Russo-Japanese war led Nicholas to impose direct monarchist rule over Finland. The reign of Nicholas II prior to February 1917 is known in Finnish history as “The Second Period of Russification”.

When Nicholas II was removed via the first Russian revolution (Feb/March 1917), the provisional Russian government returned autonomy to Finland. Internal political squabbles led to the dissolution of the nascent Finnish parliament, and the October/November revolution of 1917 led to the rise of competing parliamentary groups:

- a conservative “White” group made up of Finnish monarchists, political conservatives & the Swedish minority;

- a socialist “Red” group made up of socialist paramilitaries, Finnish Bolsheviks & militant Red Guards

The Whites declared independence in early December 1917; the Reds on December 31. Open warfare between the two groups erupted in late-January 1918, inaugurating the Finnish Civil War. To try & get foreign support, the Red Finns signed the Treaty of Peace & Amity with Lenin’s government, because the Reds favoured reintegration with Russia. Lenin encouraged this belief, because he felt that all socialist republics would eventually be united under one (Soviet) leadership.

Two days later, Soviet support was all undone due to the official signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, with Russia surrendering to the Central Powers. Finland was transferred to the German sphere of influence via the Treaty, and the Germans used their influence to stifle support for the Reds in the Finnish conflict, so as to minimize their troop commitments in the East so they could redirect their forces to the Western front. The civil war ended in May 1918 with the Whites successful; plans to install a Finnish monarchy failed when the Germans were defeated in November 1918, and the country became a democratic republic. Over 32,000 people died – 1.2% of the population, almost three times the number that died in the Spanish influenza outbreak of 1918. Additionally, there were 80,000 POWs

Two days later, Soviet support was all undone due to the official signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, with Russia surrendering to the Central Powers. Finland was transferred to the German sphere of influence via the Treaty, and the Germans used their influence to stifle support for the Reds in the Finnish conflict, so as to minimize their troop commitments in the East so they could redirect their forces to the Western front. The civil war ended in May 1918 with the Whites successful; plans to install a Finnish monarchy failed when the Germans were defeated in November 1918, and the country became a democratic republic. Over 32,000 people died – 1.2% of the population, almost three times the number that died in the Spanish influenza outbreak of 1918. Additionally, there were 80,000 POWs

The Russian Civil War ran from 1918-20, also between competing Reds & Whites; obviously, the Reds won. The effect of seeing other countries support their opponents led Lenin to make deals that would allow the Bolsheviks to cement control over their own state; they’d worry about others’ revolutions later. To avoid further conflict the damaged state was not prepared for, the Soviet government signed the Treaty of Tartu in October 1920 guaranteeing a common border with Finland. The border roughly followed the old boundary as the Grand Duchy, but also gave Finland a port on the Arctic Ocean via transfer of the territory of Petsamo.

Stalin would rectify all those gains after World War II. We’ve talked about that topic at DFO before.

March 26: The Doullens Agreement

In sum, The Doullens Conference led to an Anglo-French agreement to appoint French Marshall Ferdinand Foch Supreme Allied Commander of their forces along the Western Front. In reality, this event will be noted as one of the key reasons for German defeat in the West, and ultimately the war.

In response to the German “Spring Offensive”, launched on March 21 with “Operation Michael” (see below), a result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk & fighting finally ceasing along the Russian front, the British & French met to discuss a coordinated response to the German assault. Highlighting the ridiculousness of their efforts up to this point, the British & French had been fighting separate, uncoordinated conflicts with the Germans, which exacerbated the breadth & length of the trench-warfare stalemate in the West since 1915.

—————————————

Operation Michael,

launched on March 21, was an attempt to drive northwest through France, dividing the British & French armies, and hopefully forcing the British to retreat to the coast & back to England. Since the end of conflict along their eastern front, the Germans had been re-positioning forces into the West in hopes of one final barrage that would force either the capitulation of France or the removal of Britain from the field of conflict.

Haste was of necessity for the Germans, as the Americans had yet to commit any real forces to Europe, but Pershing’s army was expected to arrive in April. By turning the conflict in their favour before the US arrived, it was hoped that the war could be concluded before the Americans – unwilling participants as their politicians were – felt it necessary to begin shooting.

Only in 1918, and in desperation at the post-Brest-Litovsk German one-front strategy, had the idea to coordinate their forces entered their collective government’s minds. The launch of Operation Michael led British Commander-in-France General Haig to force a conference to finally decide to coordinate strategy against an enemy with only one-front in focus at this point. The politicians quickly agreed to this proposal.

It was decided that a French general would be in charge of the coordination, as it would be awkward for a British general or politician to rationalize military decisions in and for France. Marshall Foch was preferred by the British over Petain, who would instead lead the French army. On April 3rd, the Agreement was cemented at Beauvais – the Anglo-French forces would operate under Foch, and the increasing nimbers of arriving Americans would operate in France under Pershing but coordinate with Foch.

Operation Michael was stalled on April 4 outside Amiens (British textbooks) in a village named Villers-Bretonneux (French textbooks). The combined British-French armies under Foch had made their last stand here, because a German victory would have cut train lines to both Paris and the coast. They were able to hold the town and force a German retreat. A German counter-offensive April 24-25 to attempt taking the town was unsuccessful, but is notable for being the first tank-versus-tank battle in history, the Second Battle of Villers-Bretonneux.

To that point, the British had had 178,000 men killed, injured, or captured. The French totals were 77,000, and the Germans 239,000. The difference was the British & French were able to supplement their forces with the arrival of the US Army, whereas the Germans had used their remaining general forces.

One year earlier, on April 6, 1917, when the United States declared war against Germany, the nation had a standing army of 127,500 officers and soldiers. The failure of Operation Michael would mark the start of the German decline in the West, an event hastened by the arrival of the US army’s American Expeditionary Force, who had one million troops in France by May 1918, leading to their eventual surrender in November 1918. In the end, around 4,000,000 soldiers were mobilized and 116,708 American military personnel died during World War 1 from all causes (influenza, combat and wounds), and over 264,000 were wounded.

As important, but unknown at the time, the Doullens & Beauvais Agreements would set precedent for Eisenhower’s “Supreme Allied Commander” status when the Allies were planning their western front in World War Two. Because, why would they think they’d have to do this again in 20 years?

May 17: 150 Sinn Fein leaders & allies are arrested in Ireland and interned.

A.K.A – The “German Plot”

In 1914, a former high-ranking official in the British Home Office, Sir Roger Casement, set out for Germany in hopes of securing an alliance for Irish Republicans with Germany, in hopes of obtaining military assistance in exchange for distracting Britain via pursuit of Irish independence. He was seeking a quid pro quo, wherein Germany would recognize a free Ireland & help the separatists pursue that dream, and the effort Britain would need to put into quelling the state of rebellion would hopefully distract from their European efforts in The Great War.

To that end, Casement attempted to recruit Irishmen captured by the Germans as British POWs as an “Irish Brigade” to return to Ireland and fight for independence. However, he was only ever able to recruit 56 men, and abandoned the strategy shortly before the Easter Rising of 1916.

The Germans were willing to provide military assistance to the rebels, in the form of guns and ammunition, notably 20,000 rifles, one million rounds of ammunition, and explosives. However, the transport was intercepted by the British (& scuttled by its crew) and Casement was arrested trying to sneak back into Ireland. The Easter Rising failed (as an assault), Casement was tried & executed, and the British now had “proof” that Irish independence was a German plot.

Here’s a documentary on the Rebellion narrated by Liam Neeson, with insight into the confusion caused by the loss of the German weapons.

In April 1918, one member of Casement’s Irish Brigade, John Dowling, was arrested trying to return to Ireland after having been dropped off the west coast in County Claire by a German U-boat. Under interrogation, he “admitted” that the Germans were planning an assault on Ireland, in order to distract the British from the European war effort. The discovery of this “German Plot“, and Irish Republican leaders open advocacy of resisting conscription

led the Dublin Castle administration to arrest & intern members of the Sinn Fein leadership.

The irony of the situation was that, just two years removed from the British atrocities committed in reprisal for the Easter Rising, the German Plot was viewed by most Irish as little more than British “black intelligence”, a contrivance used to rationalize a policy position that needed justification. Between 1916 and 1918 British Ministers did not recognize that Sinn Fein was a popular, indigenous movement, and instead clung to the notion that it was a German conspiracy; this delegitimised it and produced a vain hope that the problem would die away if the German intrigues were crushed. The arrests of the mostly moderate Sinn Fein leadership, who acquiesced in order to win the propaganda victory,

as the more extreme members were able to flee, helped alienate the bulk of southern Ireland from the British state and led to dramatically increased support for both Sinn Fein and full independence.

Sinn Fein would win election victory later in 1918, and use the size of their victory to declare unilateral independence, kicking off – depending on where your relatives are from – the 1919-1921 Anglo-British War or the Irish War of Independence. In retrospect, the German Plot was the last step towards Irish independence, even though the British didn’t recognize it at the time.

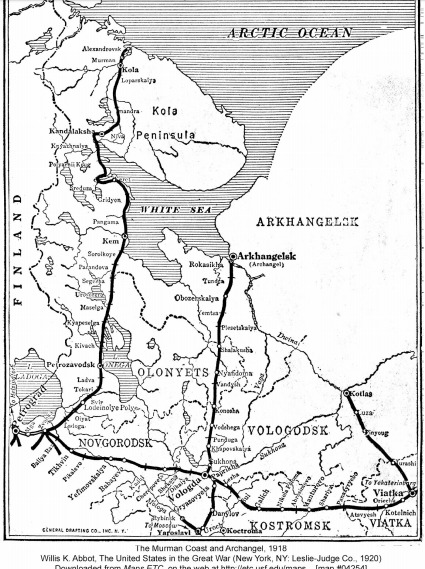

May 24: the North Russia Expeditionary Force lands at Murmansk.

In March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk formally withdrew Russia from participation in the war against Germany, freeing the Germans to devote more resources to the western front in France & Belgium. This was concerning to the British & French, because the American Expeditionary Force had not yet fully arrived; due to be 1.0 million troops by the end of April 1918, the fear among British & French leaders was that German offensives like Operation Michael might advance far enough to render arriving US troops moot. Further, the Allied powers were worried that Germany, which had recently sent 55,000 men to a newly independent Finland, would attempt to take the vital Russian ports of Archangel and Murmansk. It didn’t help that available British intelligence showed the Bolsheviks abandoning towns along the treaty lines, ostensibly to reduce the threat of German invasion at a time when the Reds were trying to shore up their defensive positions in and around major cities.

The decision was reached to send an Allied Expeditionary Force to Murmansk to try and shore up Russian defences against Germany. This force was led by British Major General F.C. (Frederick Cuthbert) Poole. Prior to World War One, Poole had served in India, fought in the Boer War (1899-1902) and the Dervish War (1902-04) in Africa, and served with British colonial forces in Nigeria. He retired as a Major on the eve of World War One. He was recalled to service soon after the war started, given promotion to Lieutenant Colonel in 1915 and given field advancement all the way up to temporary promotion to Major General in 1917. Poole was chosen for this mission because he had on-hand knowledge of the Russian situation, having been the officer in charge of the British military equipment section in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). He specifically had asked if he could be sent to Archangel to help retrieve British materiel there, and in response was put in charge of the whole mission. He left Britain on May 17th and arrived May 24th.

The decision was reached to send an Allied Expeditionary Force to Murmansk to try and shore up Russian defences against Germany. This force was led by British Major General F.C. (Frederick Cuthbert) Poole. Prior to World War One, Poole had served in India, fought in the Boer War (1899-1902) and the Dervish War (1902-04) in Africa, and served with British colonial forces in Nigeria. He retired as a Major on the eve of World War One. He was recalled to service soon after the war started, given promotion to Lieutenant Colonel in 1915 and given field advancement all the way up to temporary promotion to Major General in 1917. Poole was chosen for this mission because he had on-hand knowledge of the Russian situation, having been the officer in charge of the British military equipment section in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). He specifically had asked if he could be sent to Archangel to help retrieve British materiel there, and in response was put in charge of the whole mission. He left Britain on May 17th and arrived May 24th.

Once on the ground, Poole had specific orders. First, his small British force would ally with approximately 20,000 Czechoslovak & 3,000 Serb soldiers supposedly making their way to Archangel & Murmansk, having been promised safe passage through Russia by Lenin for the dual purpose of defending northern Russian ports and their evacuation to their third countries, notably France, which would create the 22nd Czechoslovak Rifle Regiment in the French Legion to support & organize these men.

Once on the ground, Poole had specific orders. First, his small British force would ally with approximately 20,000 Czechoslovak & 3,000 Serb soldiers supposedly making their way to Archangel & Murmansk, having been promised safe passage through Russia by Lenin for the dual purpose of defending northern Russian ports and their evacuation to their third countries, notably France, which would create the 22nd Czechoslovak Rifle Regiment in the French Legion to support & organize these men.

[These Czechoslovak soldiers had been fighting as part of the “Czechoslovak Legion“, a 60,000 man volunteer unit (supplemented by Austro-Hungarian POWs or defectors) within the Imperial Russian Army, against the Austro-Hungarians in attempt to free Czechoslovakia from Austro-Hungarian rule. They fought alongside Russian forces between 1915-17, until the Bolsheviks came to power in November 1917 and declared a ceasefire. At that point, the majority opted to join western forces in Flanders by retreating from the Ukraine & travelling to the Pacific port of Vladivostok. This majority would eventually become the fighting force that allied with the Whites in the Russian Civil War. Others were believed to be taking the shorter route between the Ukraine and the Barents Sea, where Archangel & Murmansk lay. It is these men that Poole was anticipating.]

Second, Poole was instructed to determine how far inland he could advance with the forces at his disposal, once he had secured Archangel. However, soon after his landing, it was determined that no Czechoslovak forces were headed towards Archangel and Murmansk; instead, the entire Czechoslovak force was headed to Vladisvostok, and due to German demands that they be halted from evacuating (eventually) to the western front, they were stopped by Bolshevik forces. [The skirmish that broke out on May 14 became known as “The Revolt of The Legion“, resulting in the Czechoslovak seizure of the Trans-Siberian railway, rumours of the liberation of one boxcar of the Tsar’s gold, and the rushed execution of the Romanov family at Yekaterinburg by the Bolsheviks on July 23rd, 1918, to prevent their liberation by the Czechoslovak forces.]

With no other troops at his disposal, Poole was forced to request Allied reinforcements for his position. Some 30,000 men, almost half of them British, were eventually stationed at the Arctic ports of Murmansk and Archangel under General Edmund Ironside. The majority of the troops arrived in July, and established base. Included in this number were 1200 Canadian troops, 2000 French & colonial troops, and 8000 men from the 85th Division at Camp Custer, Michigan – who were known as the “Polar Bears“.

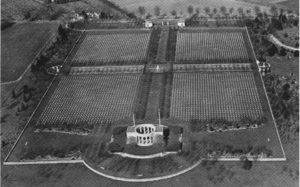

The Polar Bear Memorial, White Chapel Cemetery – Troy, MI

In August 1918, anti-Bolshevik forces led by Tsarist Captain Georgi Chaplin, coordinated and supported by Poole, staged a coup against the Bolshevik government in Archangel, setting the stage for Western participation in the Russian Civil War (1918-1920). At its greatest, Poole’s forces managed to advance over 100 miles inland, but never made meaningful progress towards the capital at Moscow. (The Civil War did, however, have the effect of reinforcing the Bolsheviks decision to keep the Russian capital in Moscow, after its move inland by Lenin in March 1918 because he feared foreign invasion.) After stalemating, a slow retreat was undertaken in early 1919, as a war-weary public in both the US and Britain demanded all troops be brought home after the November 1918 armistice. Allied troops would stay in Archangel until withdrawal in August 1919 and Murmansk until September 1919.

September 12, 1918 – The Battle of St. Mihiel – a.k.a. – “America’s First D-Day”

To quote Business Insider, the earliest known use of the term “D-Day” dates back to World War One. The U.S. Army Center of Military History identifies this distinct origin: “In Field Order Number 9, First Army, American Expeditionary Forces, dated September 7, 1918: ‘The First Army will attack at H hour on D day with the object of forcing the evacuation of the St. Mihiel Salient.'”

The Americans led the attack on St. Mihiel using the newly created First Army under General Pershing. Numbers vary, but the First Army of St. Mihiel had seven divisions numbering over 500,000 US & 100,000 French troops. It is notable for being the first offensive launched by the US Army during the war – most US contacts prior to this were reactive assaults or as part of a larger multinational contingent. This was important because Pershing had resisted allowing other countries commanders to use US troops as ‘hole fillers’ in troop commitments. He didn’t want American troops fed into the same meat grinder that the British & French had been using for the previous four years.

He devoted most of his time from US deployment after April 1917 to planning for eventual US American Expeditionary Force missions. In June 1917, to compliment the infantry divisions, Pershing announced the creation of a tank force under then-Lieutenant Colonel George Patton, who by September 1918 had two battalions under his charge.

Air Force Magazine, the choice of flyboys everywhere, describes the area this way, in its analysis of the role of Billy Mitchell, the first chief of the Army Air Force:

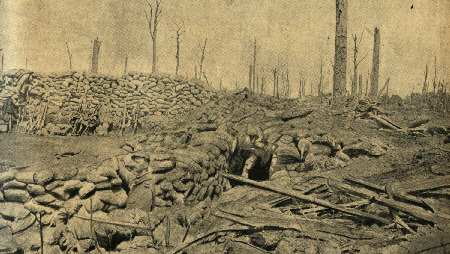

The salient was 25 miles wide at its base and 15 miles deep, extending from about 10 miles southeast of Verdun to the town of St. Mihiel on the Meuse River… In the course of four years, the German forces had diligently fortified the whole area with the usual trenches, wire barricades, and concrete pillboxes in the front line, backed up by a second line of similar works. If the Allies broke through all this, they would then be faced with the Hindenburg Line, a heavily wired series of trenches and strongly built dugouts that the Germans had equipped elaborately. Behind the Hindenburg Line there loomed the formidable fortress system of Metz and Thionville. The salient was defended by 8.5 divisions of ground troops, including a large Austro-Hungarian element.

The salient was 25 miles wide at its base and 15 miles deep, extending from about 10 miles southeast of Verdun to the town of St. Mihiel on the Meuse River… In the course of four years, the German forces had diligently fortified the whole area with the usual trenches, wire barricades, and concrete pillboxes in the front line, backed up by a second line of similar works. If the Allies broke through all this, they would then be faced with the Hindenburg Line, a heavily wired series of trenches and strongly built dugouts that the Germans had equipped elaborately. Behind the Hindenburg Line there loomed the formidable fortress system of Metz and Thionville. The salient was defended by 8.5 divisions of ground troops, including a large Austro-Hungarian element.

Despite these fortifications, Pershing readily agreed to have the Americans try to pinch off the St. Mihiel salient as the initial step in a series of Allied offensives to end the war. He was eager to both test American mettle and begin the process of hastening the end of the war & sending his doughboys home.

The Battle of St. Mihiel began on September 12, 1918 at 0100 hours. To borrow from “The Independent“, Wire-cutting crews were sent out before dawn to tackle the barbed wire. When the gloomy day broke, Pershing’s strategy of isolating the remaining Germans pincer-fashion, liberating villages one by one and retaking territory that for years had blocked train routes east from France, was put into violent, deafening motion.

Half a million men took part, in seven divisions, making it the single largest military undertaking in America’s still young history. Roughly a million shells were fired on German positions in the first four hours. As the foot soldiers and tank formations made gradual advances, teams of horses dragged the heavy guns through the mud to take the barrage forward. But while progress over nearly four days of battle was faster than even General Pershing had hoped, the cost in life, limbs and blood, on both sides, was terrible.

The Germans suffered the greatest casualties – 5000 dead & wounded; 15000 taken prisoner – but the Americans & their allies suffered 7000 casualties of their own, including 2500 KIA. The news would be a great shock to most Americans, who had not been exposed to a casualty count this high since the US declared war in April 1917. The weather played a significant factor in the casualty count, as troop movements were bogged down by the mud, and they were forced to advance from known trenches the Germans easily targeted. Further, the aerial reconnaissance Mitchell nascent air force undertook was rendered useless by the weather impacting their ability to survey the active battlefield. However, the numerical & materiel superiority of the Allied forces was too much for the Germans to overcome with their reduced numbers & morale.

The Germans suffered the greatest casualties – 5000 dead & wounded; 15000 taken prisoner – but the Americans & their allies suffered 7000 casualties of their own, including 2500 KIA. The news would be a great shock to most Americans, who had not been exposed to a casualty count this high since the US declared war in April 1917. The weather played a significant factor in the casualty count, as troop movements were bogged down by the mud, and they were forced to advance from known trenches the Germans easily targeted. Further, the aerial reconnaissance Mitchell nascent air force undertook was rendered useless by the weather impacting their ability to survey the active battlefield. However, the numerical & materiel superiority of the Allied forces was too much for the Germans to overcome with their reduced numbers & morale.

An acknowledged key to US success was their officers’ command on the battlefield. Unlike the British & French, who commanded from the safety of the rear lines, most US commanders were at the front with their units, which gave them opportunity to assess the battle as it unfolded & make strategic changes in real time. Patton was acknowledged for this ability, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his ingenuity & heroism after this battle. It was also how he came across Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, because Patton’s 327th tank battalion overran the position MacArthur’s 42nd Division was trying to nail down. The two men interacted for about two hours, an incident more fondly remembered by Patton than MacArthur.

Aside from Pershing, Mitchell, MacArthur & Patton, a US military history ‘murderers’ row’ all involved in one battle, one other notable American participant was First Lieutenant Maury Maverick. He earned the Silver Star and the Purple Heart during his service in the war, particularly at this battle & the Battle of the Argonne. He was a lawyer upon his return to the States, but later was elected to Congress from Texas’ 20th District in 1934, and hired as his congressional secretary Lyndon Johnson. He served two terms, and is notable for inventing the word “gobbledygook” to describe the jargon and long-winded government memos (that were “long, pompous, vague, involved, usually with Latinized words…”) he encountered during his time in Congress.

The St. Mihiel American Cemetery itself was dedicated in 1937. There are 4,153 soldiers buried there, with 284 acknowledged as MIA.

They are hosting a ceremony on September 22nd to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the battle, and on November 11th they will host a memorial in honour of the 100th anniversary of the Armistice ending the war.

September 26, 1918 – The Battles of the Hindenburg Line

Known as “The Grand Offensive” in France, it was a key component in the “Hundred Days Offensive”, a strategy conceived by French General Foch to begin taking the battle in the West to the Germans.

Regarding the Hundred Days Offensive, Foch wanted to use the massive troop contingents available in Europe by the summer of 1918 to begin countering the end of the German Spring Offensive in the West that had begun in March 1918 with Operation Michael in March 1918 and drifted off by the end of July 1918. The French, British & Americans each had over 1.0 million men at their disposal, and Foch wanted to coordinate assaults by each army in concentrated efforts to weaken German front lines and force their retreat back towards Germany. The Battle of Amiens on August 8 & The Second Battle of the Somme on August 15 were the initial salvos in this strategy, and Allied victory had forced the Germans to retreat.

The Battles of the Hindenburg Line commenced on September 26th, with the French & Americans attacking the Germans via the Meuse-Argonne offensive, with the British & Belgians attacking two days later in the Fifth Battle of Ypres. The AEF, led again by Pershing, had prepared for their offensive by moving over 400,000 men into the area, a mere ten days after the conclusion of the Battle of St. Mihiel. The assault began at 5:30 AM on September 26th. The preliminary bombardment, using some 800 mustard gas and phosgene shells, killed 278 German soldiers and incapacitated more than 10,000. Although this success allowed the Americans to overrun German forward positions, heavy rains turned the terrain to mud, which bogged down tanks and artillery and slowed resupply efforts, allowing the Germans to reinforce their rear positions and slow the Americans advance after their initial success. The AEF only advanced their lines eight miles by the end of September.

The Battles of the Hindenburg Line commenced on September 26th, with the French & Americans attacking the Germans via the Meuse-Argonne offensive, with the British & Belgians attacking two days later in the Fifth Battle of Ypres. The AEF, led again by Pershing, had prepared for their offensive by moving over 400,000 men into the area, a mere ten days after the conclusion of the Battle of St. Mihiel. The assault began at 5:30 AM on September 26th. The preliminary bombardment, using some 800 mustard gas and phosgene shells, killed 278 German soldiers and incapacitated more than 10,000. Although this success allowed the Americans to overrun German forward positions, heavy rains turned the terrain to mud, which bogged down tanks and artillery and slowed resupply efforts, allowing the Germans to reinforce their rear positions and slow the Americans advance after their initial success. The AEF only advanced their lines eight miles by the end of September.

But, with German forces already divided & weakened, on September 29th the British Fourth Army & French First Army attacked the Germans along the Hindenburg Line in & around St. Quentin. The British and Belgian armies advanced across the old Ypres battlefield, and in three days the Menin Road Ridge, Passchendaele Ridge and all of the familiar landmarks of four years of fighting were back in Allied hands, and the Allies had advanced ten miles. [This phase of the fighting was officially designated the battle of Ypres, 1918, but is also sometimes known as the fourth battle of Ypres.] Bolstered by this success, on October 4th, the US resumed its offensive along their front. By October 5th, the Line had been broken along a 19 mile front. On October 8, the British First & Third Armies engaged the Germans in the Second Battle of Cambrai, and further broke the Line by another four miles. The rout was on.

But, with German forces already divided & weakened, on September 29th the British Fourth Army & French First Army attacked the Germans along the Hindenburg Line in & around St. Quentin. The British and Belgian armies advanced across the old Ypres battlefield, and in three days the Menin Road Ridge, Passchendaele Ridge and all of the familiar landmarks of four years of fighting were back in Allied hands, and the Allies had advanced ten miles. [This phase of the fighting was officially designated the battle of Ypres, 1918, but is also sometimes known as the fourth battle of Ypres.] Bolstered by this success, on October 4th, the US resumed its offensive along their front. By October 5th, the Line had been broken along a 19 mile front. On October 8, the British First & Third Armies engaged the Germans in the Second Battle of Cambrai, and further broke the Line by another four miles. The rout was on.

The AEF and the French cleared the Argonne of all German resistance by the third week of October, allowing Pershing to reorganize his forces. He redrew his divisions, creating a First Army under General Hunter Liggett and a Second Army under General Robert L. Bullard. Pershing then set his duties to overall strategy and planning. The Americans were looking to cement their victories before the onset of winter, and Pershing wanted to prepare for a final Spring offensive in 1919.

General Hunter Liggett General Robert Lee Bullard

_____________________

Fun fact: Prior to becoming head of the Second Army, Bullard had commanded the First Division, a.k.a. “The Big Red One”.

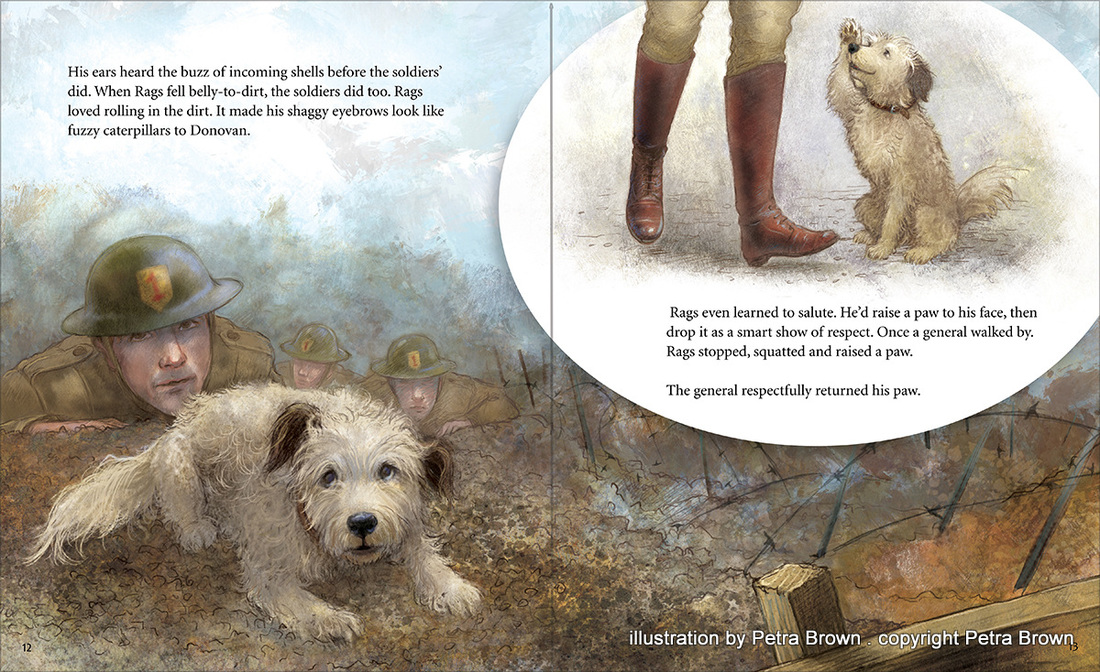

The mascot of the division was a terrier named Rags, who served at the front with his adopted master, James “Jimmy” Donovan. Rags was instrumental in relaying messages from the front to the rear, and helped US forces better target their artillery.

Further, as Wikipedia cribbed from the children’s book about Rags, when Rags was first in the front lines and came under shellfire, he simply imitated the men around him who would drop to the ground and cover their heads. “Before long, the soldiers observed Rags hugging the ground with his paws spread out before anyone heard the sound of an incoming round. The men soon realized that Rags’ acute and sensitive hearing was telling him when the shells were coming well before they could hear them.” The doughboys learned to keep their eyes on Rags, and he became an early-warning system for artillery shell fire.

He and Donovan were later gassed in a German attack, and such was his reputation (“orders from headquarters”) that Rags was given equal medical treatment and allowed to stay with Donovan through his hospitalization & evacuation back to the States. He remained the mascot of the First Division until his death, and was given a military burial.

He also became famous, having books written about him for both adults & children.

As a dog person, there is no way I was not including that stuff.

_____________________

Almost 1.25 million American troops had participated during the course of the 47-day campaign. American casualties were high—over 117,000—but the results were impressive. The 1st Army had driven forty-three German divisions back about thirty miles over some of the most difficult terrain and most heavily fortified positions on the Western Front, while inflicting over 120,000 casualties. The British & French suffered similar casualties, but the difference here was that their combined effort forced the Germans to re-evaluate their position on continuing to fight. This was the American influence on hastening the end of the war.

As early as September 29th the Kaiser was told that German victory in the West was no longer attainable. The scale & speed of the German defeats led military leadership to begin considering suing for peace, to avoid bringing the destruction of France onto German soil. The British, French & Americans had hoped their July Grand Offensive would push the Germans back to at least the Hindenburg Line, if not back to the German border, by the time winter forced a temporary break in the fighting. Instead, when the British, French & Americans were in the middle of planning their Spring 1919 offensives, the Germans – wracked by morale problems & the influenza epidemic – made their approaches for an armistice. It was only a 47-day campaign because it ended – as did all fighting – on November 11th.

November 9, 1918: Kaiser Wilhelm II Abdicates

On September 30, 1918, the German military command informed the civilian government that the war was essentially lost, due to the Entente Powers overwhelming military superiority – in large part because of the arrival of the Americans en masse between April 1917 and January 1918. They requested the civilian government begin peace negotiations; in response, the civilian government resigned. In the aftermath, on October 3rd Prince Maximilian of Baden was installed as Chancellor and he began correspondence with US President Wilson regarding surrendering based upon his “Fourteen Points”.

[Prince Maximilian of Baden was no idiot. He knew that the British & French meant to punish Germany for its conduct during the war, and make Germany “pay” for “starting the war”, in the European custom of forcing the loser to compensate the “victor” for all costs incurred during the conflict. He hoped that Wilson would have influence in preventing Germany from being pillaged by its conquerors.]

Wilson indicated that negotiations could only begin upon the abdication of the Kaiser. Prince Max wrote to the Kaiser on November 6th asking him to accede to this demand, as it was the only way to prevent the war from entering German soil. He also pointed out to Wilhelm that a revolution (not unlike that which swept Russia) was beginning to foment on the streets of major German cities, having been triggered by the Kiel Mutiny on November 3rd. Instead, the Kaiser argued that he should head to the front and lead German forces back into Germany, allowing him to be viewed as a solemn figurehead – which he hoped would allow him to resign as German emperor but keep his title as King of Prussia. To counter this stance, Chancellor Prince Max had the German command inform the Kaiser that they could not guarantee his safety out in the field, and that the soldiers would not march behind him if it was to be seen helping him retain his throne; the Kaiser dropped the issue and fled to military headquarters in German-occupied Belgium.

On November 7th, Chancellor Prince Max went to meet the head of the largest political party in Germany, Social Democratic leader Friedrich Ebert, to discuss transition to a civilian government. Ebert felt that the best way to prevent a communist revolution was for the Kaiser to swiftly abdicate and for a civilian government – initially led by him, with elections to follow – to take over and begin armistice negotiations with the Western allies.

Word was sent to the Kaiser about these conditions.

While he vacillated on a response – he still hoped to retain his Prussian title – on November 9, 1918, Prince Max and Social Democratic politician Philipp Scheidemann made separate speeches announcing the Kaiser’s abdication, something that had not officially happened yet. Prince Max made his speech to hurry the Kaiser up; Philipp Scheidemann made his speech in response to communist threats to unilaterally declare a German soviet republic. Prince Max then resigned as Chancellor, Ebert took over and declared a German republic, and the army informed the Kaiser that they would not prevent him being captured and turned over to the Allies.

The Kaiser then announced his abdication and fled to The Netherlands, under the protection of Queen Wilhelmina, a distant cousin via Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, the eldest daughter of King George II (reign: 1727-60), who is of the Hanover line of English monarchs. Under the new Republic, all other regional German kings, princes & dukes were forced to relinquish their royal titles. His abdication was formally published on November 28, 1918, ending the reign of the German monarchy.

He lived out his days in exile, prohibited from leaving The Netherlands due to articles in the Treaty of Versailles demanding his trial for war crimes. He lived in Huis Doorn, an estate he purchased from Baroness Ella van Heemstra – the mother of Audrey Hepburn.

The Dutch government allowed Wilhelm II to remain in Netherlands under strict conditions:

- He had to stay in House Doorn and was only allowed to move freely within a radius of 15 kilometers around the House.

- He had to refrain from making political statements and his mail was regularly checked.

- He was also under permanent police surveillance.

————————————————————

[In 1919, during the Versailles negotiations, the Allied governments – led by Britain, France, Italy, United States and Japan – established a “Commission of Responsibilities” to make recommendations about trying German leaders for violations of international law during the course of the war. In the Treaty of Versailles, Articles 227-230 outline these conditions and procedures. {FYI – Article 231, the “War Guilt clause”, is the most famous tract in the Treaty, and is what most historians point to when looking for causes of World War Two.} Article 227 specifically made mention of the Kaiser as a “war criminal” and demanded his extradition from The Netherlands for the purposes of being put on trial for crimes committed in his name during the war. The request for extradition was made on June 28, 1919, the day the Treaty was signed; the Dutch refused, claiming that act would violate their neutrality.

The Leipzig War Crimes trials went on from May 23 to July 16, 1921. Over 900 names were presented for possible trial; only 12 were actually brought forward. Since I’m lazy, here’s what Wikipedia had to say about their trials:

- Sergeant Karl Heynen, charged with mistreating British POWs. He was sentenced to a brief prison term of ten months.

- Captain Emil Müller, charged with mistreating POWs. He was sentenced to six months in prison.

- Private Robert Neumann, charged with mistreating prisoners of war. He was sentenced to six months in prison.

- Commander Karl Neumann of U-boat UC-67 who sank the hospital ship Dover Castle in compliance with superior orders. He was found not guilty due to the fact that he was following orders.

- First-Lieutenants Ludwig Dithmar and John Boldt, charged with war crimes on the high seas. They were two officers of the submarine SM U-86 that had sunk the Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle and then machine-gunned survivors in the lifeboats. They were each sentenced to four years in prison.

- Their commanding officer, Helmut Brümmer-Patzig, had fled to the Free City of Danzig and was never prosecuted.

- Max Ramdohr, charged with crimes against the civilian noncombatants in occupied Belgium. He was found not guilty.

- Lieutenant-General Karl Stenger and Major Benno Crusius, charged with mistreating French POWs. Stenger was found not guilty, while Crusius was sentenced to two years in prison.

- First-Lieutenant Adolph Laule, charged with crimes against the civilian population of occupied France. He was found not guilty.

- Lieutenant-General Hans von Schack and Major-General Benno Kruska, charged with mistreating POWs. Both were found not guilty.

The legacy of the Leipzig trials is that, although viewed as a failure because they didn’t put anyone of actual importance or command on trial, it did set a precedent for the post-WWII Nuremberg & Tokyo Trials.]

————————————————————

Throughout his life he believed that Jews were perversely responsible, largely through their prominence in the Berlin press and in leftist political movements, for encouraging opposition to his rule. Until his death in exile in 1941, the Kaiser spread venomous poison where he could: The Jews were to blame for his downfall, as were the socialists—he alone was right. (The Kaiser’s allegations against the Jews comes primarily from the stereotype of Jewish intellectuals being leading Russian and German communists.) He spent his time in exile harbouring a secret hope to return to Germany and resume his place of Prussian honour, or at the least serve as a figurehead over the new Republic.

Reflecting and encouraging the sentiments of all too many Germans, he saw in Hitler the new man chosen by providence, a savior after the treachery that had caused Germany’s defeat. His second wife, Hermine Reuss, maintained contact in Germany with influential people to discuss and prepare for a possible return. To this end, there was also contact with influential Nazis such as Hermann Göring (who visited Wilhelm in Doorn) and even Adolf Hitler. By all accounts, Hitler simply ignored these requests, because Hitler was a WWI soldier and blamed the Kaiser for Germany’s defeat, and eventually the Kaiser himself gave up hope of any return.

He died in June 1941, during the German occupation of The Netherlands. He was buried on the grounds of Huis Doorn, as he requested his remains not be returned to Germany until the monarchy had been restored.

Huis Doorn was seized by the Dutch government after WWII as a war prize, and is run today as a rijksmonument, or national heritage site.

Here are the Tombs of the Unknown Soldier in Ottawa,

and Arlington.

To close, the classic poem by John McCrae:

I hope you found these somewhat educational, and will do the history of the men who fought & died in this conflict the honour of attending a ceremony tomorrow. In the words of Robert Laurence Binyon,

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

I read all of these the first time and I just read all of them again. Outstanding.

Hail SHAN’KLHOR!

Theae posts were excellent and I enjoyed reading them throughout the past couple of years.

A lot of people don’t realize how much WWI and its aftermath affected the modern Middle East, some of which can be felt today.

I have a book on that, very interesting, but a difficult read and super small type. So I pick it up in fits and starts,

Fucking Sykes-Picot Agreement, France and Britain own this Middle East clusterfuck shit.

I absolutely loved these. Thanks so much for writing them!

SAME. I done learned sommet every single time.

Defensive struggle in Norman: Combined 62 points and 811 total yards … at half!

Is there an echo?

c’est magnifique! It’s a damned shame we spend so much time and energy on WWII that WWI is largely forgotten by most. Excellent, and important work.

/dick joke

//gambling lamentation

Every time I read the various books I am still amazed at the human meat grinders many of these battles were and the total disregard for lives that the lack of exploring different tactics indicated.

rags the war dog was a rocking war dog!

https://www.dancarlin.com/hardcore-history-series/

https://www.iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-london

Ours not to reason why, ours but to do and die.

This was also uttered by Randy on the toilet about a day after he had the pizza with extra cheese. He died.

https://www.toilet-related-ailments.com/heart-attack.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toilet-related_injuries_and_deaths

Not as dangerous as the trenches, but still.

Wonderful to see high energy Trump honoring the sacrifice of American doughboy.

/puts hand to earpiece.

Well it appears the mud of Flanders field has defeated the American President. Maybe we’ll have our executive there for the 200th anniversary.

Who knew it might rain in France in November? Totally an acceptable reason to blow off the USMC birthday and Armistice Day

Don’t worry he’ll honor Gary Cooper for capturing the Kaiser all by himself.

ah mean BONE SPURS HURT u snowflaek smgdh