I grew up in Southern California. The 80s and 90s were a glorious time to live in Los Angeles. Hell, every decade has been a great time to live here, but, in particular, those years were specially great because of the music, sports, and culture going on around L.A. at the time.

I’ve mentioned before how my mom taught me about Time and Place. Those years and this city showed me that was true. The experiences I’ve had will never be repeated again and I’m glad I had them.

Ok, that’s nice, Balls, you may be thinking. Can you get to the point, please?

Mai oui, je suis désolé.

One of the major influences in my aforementioned formative years was surfing and beach culture. Growing up within a forty minute drive of the beach was awesome. I can’t remember the number of times I drove down to the beach with my friends as a teenager and spent the day there.

Living in the Pasadena area, we usually went south to Huntington Beach. We would watch the surfers and go out in our boogie boards trying to get better in the water and hoping someday we could get enough money to buy surfboards and wetsuits and be out there with the others.

I wore beach clothes (still do to this day) and consumed everything beach-related. On one particular trip, we stopped somewhere (a gas station? maybe a surf shop? I don’t remember.) and I purchased a surf magazine.

It wasn’t just any surf magazine, though. Back in those days, there were magazines and there were ‘zines. The magazines were pretty corporate and included Surfer, Surfing, and a couple of others. The ‘zines were usually local productions run on small budgets with articles by aspiring writers. The music industry had them, the art industry had them, and the surf industry also had them.

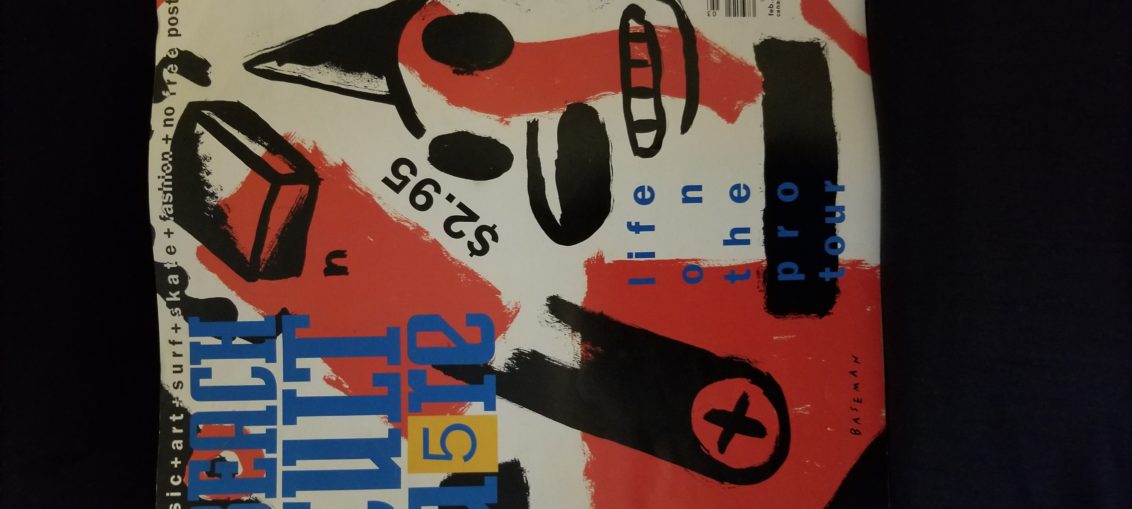

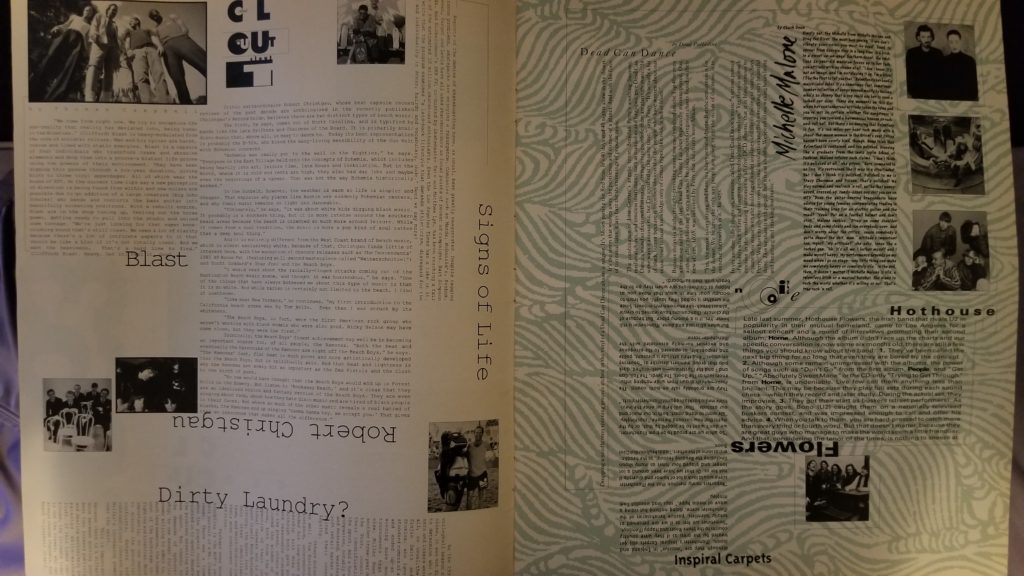

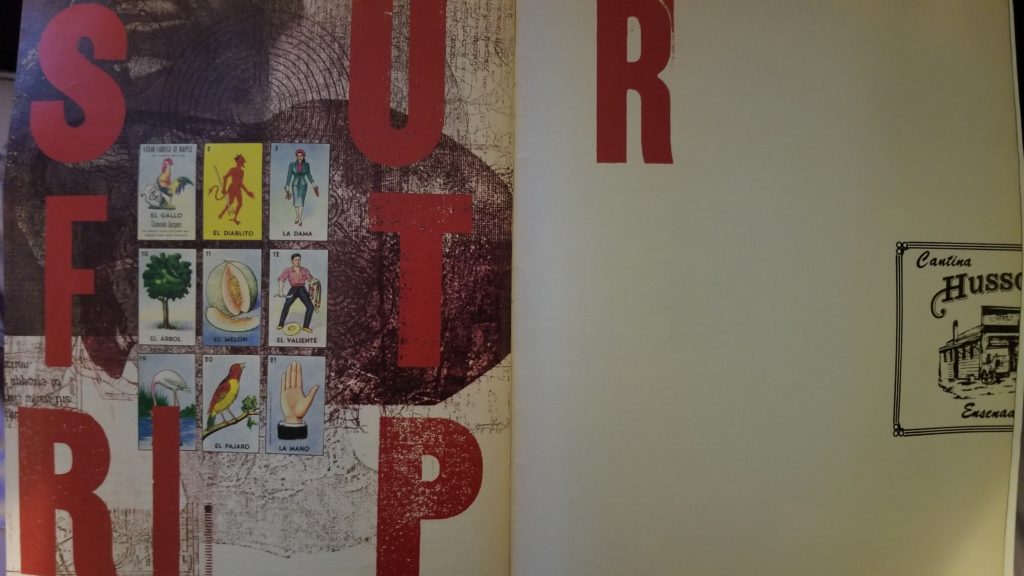

The banner image above shows you that particular ‘zine that I bought and have held onto for these many years. There were many cool things that I liked about it. They used many different types of fonts. They arranged the words and paragraphs in complicated ways where you had to take an effort to figure out how to read the article. They also had great pictures and artwork. Here’s an example of the layout:

In that issue, there were a couple of long-form articles that stuck in my head. One was a love story, though, of course, unconventional. The other was about a surf trip to Baja, Hussongs Cantina (from where everyone I knew growing up had a t-shirt), and a girl.

They really struck a chord with me and made me want to write something that could stick to someone through time like they did with me.

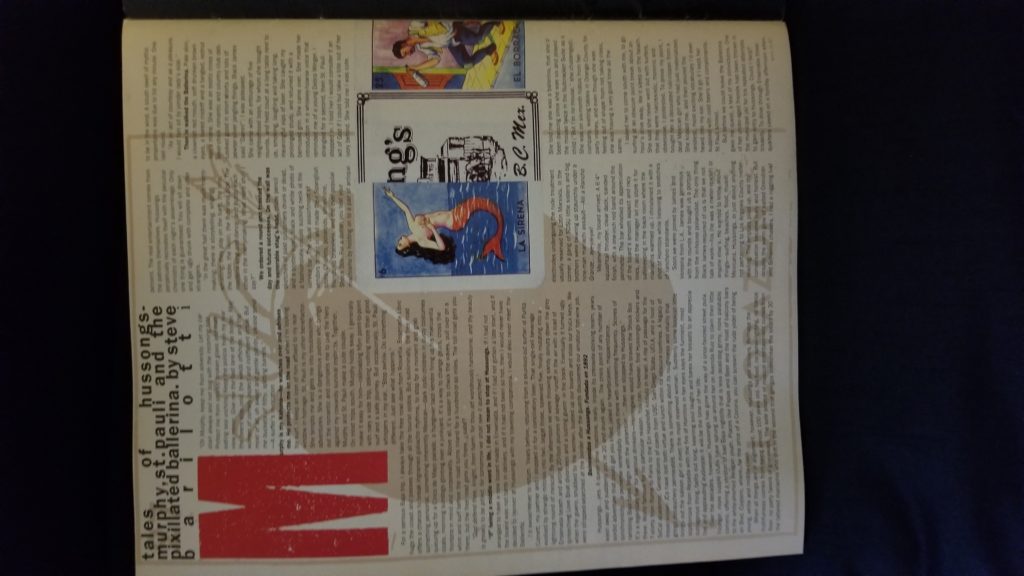

So, today, I am bringing you the surf trip story in all its glory. The pictures below show you the original text and art so you can see how it was published. I don’t think my phone camera is good enough for you to read the article from the photo, so I’m rewriting it below.

It’s funny, because in the “Jump Page”, as they called it, the publisher/editor, Neil Feineman, writes about the answer to the question, “What exactly is this magazine all about anyway?”

His answer runs very similar to what I think is the reason we started DFO in the first place. It’s about hearing from a range of people discussing subjects and interests that run the gamut.

Even back in the early 90s, he was talking about how “In today’s times, where information is controlled, power is concentrated, and conformity is encouraged…there’s a definite chill in the air. And the only way to stay warm is to find a beach of your own, huddle around a home-made fire, and hope that the only ones who find out about it are friends.”

That’s DFO to me. That’s why we’re here. And that’s why I write here.

Here are the pictures with the original article:

The writer is Steve Barilotti. He is a world-famous writer/photojournalist/editor that wrote for Surfer Magazine for a number of years and has written books about surfing and surf culture. I could not find the article online, so I am retyping it, word for word, so that you can enjoy his writing. All credit goes to him for writing an article that I randomly found on a random beach trip and that encouraged me, after all those years, to take a chance and write for DFO .

Time and Place, man. Time and Place.

Enjoy:

tales of hussongs- murphy, st. pauli and the pixilated ballerina.

by steve barilotti

“Oh Murphy, keep me from adversity. Let my car start always and not bog down with the incoming tide. Protect me from sharks, broken glass and man-eating sea urchins. Keep the policia from my rear view mirror. Give me the fast lane at the border. May the beers stay cold, the winds offshore, and women of comely aspect and indifferent virtue. But, most of all, oh sweet and gentle patrón, please send me buckets of filthy, spitting barrels.”

– A surfer’s invocation

Murphy is my Kahuna – he watches over and advises me. He protects me on the road when I’m looking for surf. I keep an icon of him affixed to my rear window in homage. St. Pauli is my other benefactor. She tempts me and gets me into troublesome adventures. She is a dangerous patrón who brings out the romantic and compels me to play the hero against my cowardly survival instincts. Together, Murphy and St. Pauli make a cute couple.

On most trips south, Murphy holds sway. I generally make it easy for him – railroading from point-to-point with nary a side trip, asking nothing more than good surf and safe journey. But occasionally, St. Pauli whispers in my ear, “Stop awhile. Do something different. Just see what happens.”

For a serious Baja trip, I always take the free road down from Rosarito. Ensenada Libre hugs the coast and passes through all the tourist ejidos. But subliminally, the free road offers a chance to break ingrained gabacho rhythms, to stop for a moment and grab something personal, something inherently Mexican – dark indio children in dusty costumes queuing up for a Cinco De Mayo parade, a hungover taco vendor firing up his manzanita coals, morning sundogs glinting over a junkyard. It’s a way to change gears, cross the frontera in mind and corporeality. Above all, it’s easier to check the waves, pull over on a whim and surf before the road turns inland for a hundred-or-so miles. The toll road gets you there, but the free road gets you there. ¿Sabe?

“God defend thee, knight, from harm: for thou art wondrously handsome, and thy beauty is greatly to be pitied, for tomorrow we shall see it quenched.”

“If” being a middle word in life, I did not mean to stop at Hussongs. If I had not arranged to have a new board made in Ensenada, and if I had not gotten a late start, and if the board was not tardy in delivery, and if it had not been so hot, then I would never have decided to layover at Hussongs with my traveling companions. I would also never meet the Ballerina.

I’d sworn never to return. Years before, returning home from a skunked-out surfari at Punta Colnett, my partner and I stopped in for a conciliatory beer. That single-cell beverage evolved by strange mitosis into two, begat three, spawned five, finally mutating into a lighting round of mescal. By the afternoon we were throwing sandy donuts down the grey Ensenada beach and arcing 20-foot plumes of sewage runoff in the air with a load of screeching Love Boat divorcees and a lusting güero in the back. Eventually it turned ugly when the güero, snubbed by the women, busted up our boards and stole our truck keys. We were stripped-searched at the border after the guards discovered our amateur hot-wire job.

Bienvenidos a Hussongs. Fundada en 1892.

Hussongs…yes. A queer time machine, really. Inside its creosote-stinking realm, years wash away and suddenly you’re 20 and drunk again. The crisis point of any number of sordid adventures that could get you killed, jailed or heartbroken. Happenstance… synchronicity… a perverse serendipity occurs there with unrelenting frequency. Scores of rambling Baja tales begin with the preamble, “…then we stopped by Hussongs.” It’s a legendary bar for serious drinkers – Hemingway would have braved the Shock Box there. World famous for no particular reason. You can, however, find Hussongs stickers and T-shirts from Rome to Paris to the Ein Hashofet kibbutz in Israel. A rite of passage for the SoCal academic. Generations of coeds from USC, San Diego State, UCLA, and a host of lesser-known JCs have lost both virtue and lunch within its obscura confines. A legacy of gringo debauchery permeates. There is something about its roughness and vitality that brings out the saloon girl in even the most reserved woman. Suddenly some bookish little sophomore from Reseda with the fire of Hornitos in her eyes says the funniest, most outrageous thing, belts out long, keening soul laughs and bares her breasts to an appreciative and applauding audience. It will be the time of her life.

Over the decades, however, Hussongs has gone the way of the once-favored street puta. Younger, more supple clubs have sprung up around her on Avenida Ruiz to claim their little corners, offering a version of bad Baja nightlife that is less dead-dog grimy, more palatable to the white-shorted Reagan youth. Places like Papas and Beer and the host of balcony bars on Blvd. Costero, where, for the price of a Corona, you can scream the rude yodel of being young, white, and middle-class.

When all things are in alignment, however, Hussongs still delivers. Perhaps the truthfulness comes from being almost 100 years old. No food, no servo-lighting, no dance floor, no party favors or giveaways. The sole source of musical entertainment comes from the tattered mariachis who drift in the second that gringos outnumber the locals by 30 percent. The real entertainment comes from the patrons themselves. Hussongs perpetually recreates itself with the peculiar chemistry of each night’s assemblage. Only one thing is guaranteed: You will sit down and get ugly drunk with complete and utter strangers.

“In the great hall there was much merry-making; there is storytelling, singing, whistling; they play on the harp, the rote, the fiddle, the violin, the flute and pipe. The maidens sing and dance, and outdo each other in the merry-making. What more shall I say?”

We ordered a round and toasted the day and future successes. On the wall was the venerable stag’s head, crude pencil sketches of past customers drunk or dead, and a poster-sized, black and white photo of a fashionplate couple sucking neck at the service bar. The usual assortment of vendors drifted in and made their Spanglish touts: Chiclets, polaroids, shoeshine, friendship bracelets, and the ever-popular Shock Box. For a dollar, you test your machismo by holding on to a pair of antique electrodes undergoing the rude treatment usually reserved for Latin Marxists. In the corner, a gang of SDSU little sisters and big brothers were bearing up staunchly under a nine-man mariachi assault – Alli a Rancho Grande… aye-yai-yai!

Meanwhile, my board arrived. A 6′ 4″ squashtail thruster, clear deck, sanded finish, with a one-inch red band around the perimeter. The bar whistled its appreciation of the board’s smooth aspect and racy lines, and the manager let me store it for safekeeping in the back room where the mariachis warmed up. I christened it with a shot of Hornitos while listening to snatches of ranchero standards.

Soon, we were joined by James and Vereena from L.A. James was generous with the rounds and bought us a portrait from the in-house polaroidist. The only thing Black James required of us is that we not talk of work – his (he was a meter-reader) or anyone else’s. He wanted to know about things – surfing, beaches, food, music, Mexicans, Hussongs, or just about anything not pertaining to Los Angeles County meter-reading. The empties piled up, and the conversation became lively and honest. But despite the warm glow of salted Orendian and Bohemia chasers, I had a niggling lust to be in the wind. A south swell of mythic proportions was due to hit any minute. One last round.

As an act of courtesy and as a pleasure, I would fain sit by yonder lady’s side.”

Then in walked the Ballerina. Pale skin, a clownish red mouth, soft drunken brown eyes, a bared midriff and a tangled, rednut lion’s mane. She was an exotic cross of biker-chick romantic and country club deb. Looked good in short shorts and lots of pewter-silver jangling things. Black James said, “Damn!”; I was poleaxed.

She came with an entourage of five neighborhood boys, for whom she bought rounds, and held court at a long table next to us, smoking, laughing and taking long meaningful sips of beer. She caught my prolonged study, and returned it with a bemused grin. She came over. She made her introduction in a whiskey-hoarse voice that reminded me of a young Debra Winger. I strangled for a second, then St. Pauli stepped in. I told her I would consider it an act of God if I could but take a bite out of her ivory behind. She told me it was cute.

She told me she was a ballerina, that she’d been dancing since she was six and played the mouse twice in the Nutcracker Suite as a child (“But I’m no mouse,” she challenged). She was on a six-month hiatus from her company, waiting tables in Orange County for party money, and even though she was feeling out of shape from not taking class, she was having a very good time all the same.

I asked her to come south with me, to go surfing at an obscure point break about an hour’s drive away. We’d sleep on the beach. She said she never went out with surfers, that they were narcissistic, moronic, and obsessive. I protested. To prove my point, I bought her a decorated nail-clipper from a deaf Mexican girl who had just materialized. She kissed me, and then poured the randiest most exciting vocabulary I’d ever heard in my ear. She’d go if I kept her supplied with cold beers and compliments. St. Pauli smiled.

But before we could leave the Ballerina gave me a quest, a test of my convictions. One of her under-aged friends had been thrown in the municipal jail for his repeated attempts to gain entry to Hussongs. Could I help? Insanity. To drive through Ensenada three quarters yawed on a holiday afternoon when everyone on the beat had carte-blanche to muscle any tourist who even thought of getting stupid. And not only drive through the congested morass of cars, taxis, buses, trucks, horses, handcarts and helado vendors that was Ensenada at critical mass, but to lurch my babbling carcass into the belly of the Gila monster itself – the Municipal Police Station – in full surfer drag. Idiocy!

But in situations like this, it is fatal to think. Love demands continuous and bold action, like running stop signs and performing three illegal U-turns. We bailed the errant boy out, returned him to his motel, made him and the others promise to leave the Ballerina’s new black IROC alone, and went south with a shout.

“They rode until nightfall without coming to any town or shelter. When night came on, they took refuge beneath a tree in an open field. The knight bids his lady sleep, and he will watch.”

In retrospect, it was wrong to have taken the Ballerina out of Hussongs. she thrived there, drawing sustenance from the smoke and mescal. Outside, she existed only as a shadow. But I was selfish. I wanted her away from the boisterous crude crowd, all for myself.

So, I popped a beatific imported beer in the doorjam and offered her a seat. She acquiesced with a dry laugh. Whenever the conversation drifted, I simply pulled over and beheaded another chilly one.

Having missed the ejido turnoff twice, and been delayed by frequent stops for tacos, beers, aspirin, Pemex, bladder relief, French lessons and thoughtful interludes, we didn’t find the point that night. Near dusk, though, we did find what she thought was a buffalo range. After clearing the area of any potentially-aggressive bison, we pulled next to an unused buffalo wadee and made love on the warm hood to the serenade of downshifting cattle trucks.

When we finally made the coast, a three-quarter poxy moon lit a pancake sea. The surf: pitiable ankleslappers. After a stretch of white-trash resort property, the road turned really vile, ripping the springs out of my pudding little suburb buggy. When the beers ran out, I pulled over to a convenient bluff overlooking a horseshoe cove. I had just enough strength to throw up the tent and hoist the snoring Ballerina into it. She curled up and shivered under three Mexican blankets. I stood a dogwatch with my patróns.

The next morning I attended to the baptismal rites of my nascent board. It was rainy, overcast, and a pod of dolphins patrolled the lineup. On the walk down to the cove I passed a half-eaten shark and a cairn of disposable diapers. Some sloppy three-foot waves crept in over the reef. I floated the board in the cove, applied the first wax coat, and offered a prayer, “Oh God, don’t let it paddle like shit.” I shoved out through the needle-eye pass.

The prayer took. The board worked beautifully, catching waves effortlessly, and filleting the lifeless junk like samurai steel. I was in love: with the Ballerina, with my new board, with God’s perfect and most wondrous firmament. I caught six waves, never fell once, and I bellied in. Back at the camp, the Ballerina awoke, cursed the light, stumbled over and kissed me. I started a fire, sipped tea, and thanked the little one.

The return to Ensenada was purifying – a beautiful day without a hint of wickedness or subversive intent. The Ballerina attempted small talk behind coal-black glasses despite hunger and hangover. We made it back without incident… almost. A block from the motel I became distracted by the Ballerina and rear-ended a fussy mini-truck full of Mexican-born Marines.

The owner was big, pissed and ready to bring on an overdue shitstorm when Murphy stepped in for the last time. He simply admitted to the burly 20-year old corporal that I was a lovesick idiot, and I had fucked up Big Time. Sorry. The corporal shuffled and bellowed, sighed, closed his eyes and waved me on. Back at the dirty-pink motel, we traded pleasantries in the courtyard until the Ballerina’s desire for a shower overwhelmed her. She gave me a kiss, a dubious phone number, and an hour of light to joust with the overdue south. I was anxious not to overstay the moment, to leave on a good exit line. She said she was going back to Hussongs. I asked her to be careful.

I took the free road home. The south never showed and somewhere near Otay my front-end developed a horrible shimmy.

I called the Ballerina once. I was informed by an irritated ex-roommate that she’d moved out and, no, she didn’t know where… L.A. somewhere. I returned to Hussongs a month later. My partner and I were surrounded by a squad of off-duty city policia on a happy hour stakeout. The mariachis sounded forced and we were accosted by a surly meatcutter from Chula Vista who acted like he was on the run from a 7-Eleven rip-off. We left after two hours with beer still in the bottle. I caught a vicious cold on the way back.

I never saw the Ballerina again.

***

And I never found that ‘zine again.

(93/69)

Uf. Great stuff all around. The beach is great. Knowing the beach is 10 mins. from my Apt. walking is an unquantifiable luxury.

Man, that’s a good one. Thanks for the transcription

Took the former missus right to Rosarita Beach back in the early 90’s. Stayed at the Rosarita Beach hotel. Rode horses on the beach, went to Papas and Beer and Senor Frog’s. Bought cheap fireworks that could start a war in some countries. Drove to Ensenada, visited La Bufidora, had the best roadside lunch ever of dollar tacos and Dos Equis and took the free road back to Rosarita. Last night went to Peurto Nuevo for family style lobster dinner and margaritas and spent the last night at the Hotel California. Crossing the border we claimed only a pair of marionettes failing to disclose the trunk load of cheap liquor and fireworks.

Easily the best memory of my only marriage.

“…and spent the last night at the Hotel California.”

Such a lovely place.

You really did the Baja experience right! The one Baja thing you didn’t note were the cold coconuts on the side of the road. So delicious and refreshing!

This is excellent – brb gonna add a Hussong’s sticker to the back window of my Baja.

Cue the “Surfing Obama” song:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pcHI_lTmog4

The new Thor movie looks weird…

Oh man, I remember Hussong’s. I grew up in Santa Barbara in the 70’s, and Baja was a rite of passage. We’d have a suitcase filled with old Playboys and Penthouses to trade with the locals for beer; cash was mostly used for gas. There weren’t as many places in Ensenada then… I don’t remember Papas and Beer until the early 8o’s, but I never really went there much. It was always about Hussong’s and yes, I had the bumper sticker.

Love the story. Thanks for reprinting it. I’m thinking that, depending on how the next year or two play out, it might be time again for life south of the border. Just like Andy Dufresne. I will probably stop at Hussong’s on the way down.

Hum, I always found a way to get beer AND keep my stash of Playboys and Penthouses, even the ones with pages stuck together.

*Sold weed.