February 26, 1919 – The Grand Canyon Becomes A National Park

First afforded Federal protection in 1893 as a Forest Reserve and later as a National Monument in 1908, Grand Canyon did not achieve National Park status until 1919, three years after the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, becoming the 14th US National Park. In reading up on the history of the Canyon, I learned a great deal about the people involved with its history, so there’s more here than just coverage about passing a law to protect a big hole. I hope you enjoy it.

The Canyon has been occupied since the Paleoindian period, about 11,500 years Before Present (or approximately 9500 BC / BCE). They were nomadic people, who moved seasonally across the range, via the river corridor, in pursuit of sustenance. Subsistence farming didn’t occur in the region until about 3500 years Before Present, and involved the development of maize (corn) as a staple crop. This involved planting seeds in areas of annual flooding, and returning to those areas to harvest the crops before travelling to their winter refuges. Further horticultural expansion into beans & squash helped transform a nomadic society into a sedentary one, with permanent settlements becoming established in the canyon about 500 AD, as based on discoveries of storage cisterns & granaries. In archaeological terms, the evolution from the nomadic to sedentary existence – where cave pueblos emerged – is known as the Archaic period, and the period of establishing sedentary residential villages is known as the Formative Period.

By the 10th century AD, surface pueblos emerged, and as populations expanded, these structures added rooms, further establishing & cementing sedentary populations. Trade in ceramics and food staples occurred along existing routes, but as populations in these villages expanded, some populations migrated beyond established boundaries, opening up new territories for settlement. By the 1300s, both sedentary (Pai & Paiute) & nomadic (Hualapai & Havasupai) tribes had well-established footprints in the canyon.

The first Europeans to reach the Canyon were Spanish explorers commanded by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado,

In pushing north, what they actually came upon was the Native American pueblos of present day New Mexico Zuñi tribe.

What they were looking for. What they likely found.

What remains.

Modern thinking is that de Vaca and de Niza confused the colour of the pueblos in the sun with a gold exterior, and that hearing about seven settlements with the same exteriors gave rise to the legend of “golden cities”.

Nonetheless, July 1540 found Coronado conquering the Zuni village of Hawikuh, after being denied entry, in what the Spanish referred to as the “Conquest of Cibola”. Using “Cibola” as his base of operations, Coronado sent out survey teams to try and find other cities – and hopefully the riches the legends & stories promised were out there. One of these missions, led by Garcia Lopez de Cardenas, didn’t find more cities of Cibola but did become the first Europeans to explore the Grand Canyon. They came upon the south rim of the canyon, somewhere between present-day Desert View and Grandview Point, but were forced to return to Cibola because of time constraints, and the fact that they couldn’t find a safe way down to the river from their position.

[Fun facts: after Coronado left Cibola in the winter of 1540, heading east towards the Rio Grande, he came across the pueblos at Tiwa and Pecos, which afforded him the ability to both settle in for the winter and, with his guides, travel to the Great Plains to see the buffalo herds.

In seizing a pueblo as their winter camp, and taking supplies from the reticent local tribes, he triggered what became known at the “Tiguex War” between the Spanish and the Amerindian people of New Mexico & the Rio Grande. The larger Spanish force overwhelmed the isolated villages & opponents with their relatively basic Amerindian weaponry (compared to Spanish guns), forcing them to abandon their villages & relocate to the Great Plains (now Kansas). After the war, the European discoverer of the Grand Canyon, Garcia Lopez de Cardenas, was tried by the Spanish for the war crime of burning prisoners alive at the stake after capturing the pueblo of Arenal. He was convicted, sentenced to seven years in jail, and banished from the Americas.]

After the Tiguex War, the Spanish abandoned their outpost at Cibola, and no other Spaniard would return to the region for nearly three decades.

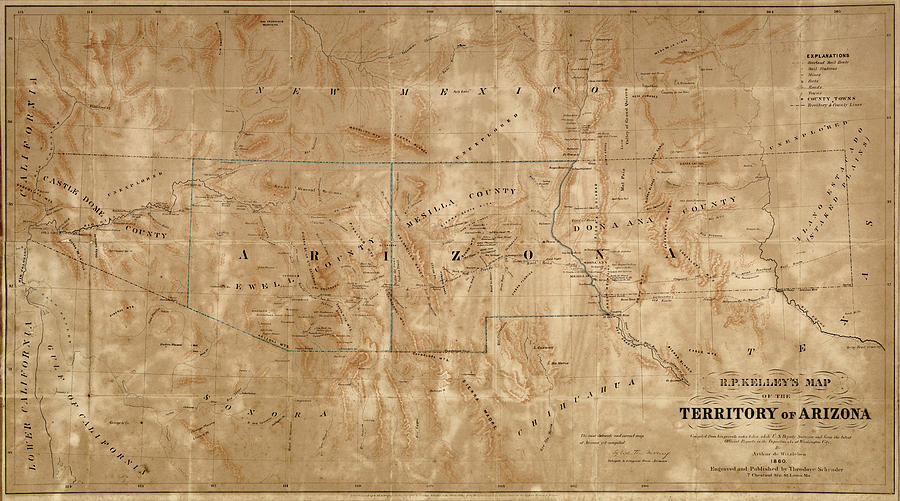

The “modern era” of American exploration of the canyon didn’t occur until 1858. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848 granted the US the right of free navigation of the Mexican parts of the Colorado (& Rio Grande) river needed to access its territorial portion. [Because the US beat Mexico in that war, the US declined to offer Mexico the same privilege.] In 1857 the US government commissioned Army First Lieutenant Joseph Christmas Ives, of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, to explore the river area to determine its usefulness as a trade route to the interior US territories.

Ives had arranged for his mission’s supplies to be sent ahead of him by ship to San Francisco, where he would head overland. From there he would set out for the Gulf of California and build his ship – a fifty-foot, specially built shallow-draft paddle steamer called the U.S.S. Explorer – at the mouth of the Colorado River before heading upriver to Fort Yuma. He left San Francisco on November 1, 1857, arriving at the mouth one month later – the trip delayed by extreme winds blowing down the Gulf, sometimes limiting their schooner Monterey to 20 miles advance per day. When they arrived at the mouth, they proceeded to assemble the Explorer & then sail north to Fort Yuma.

He launched his mission from Fort Yuma, Arizona Territory in January, 1858. [Fun facts: Yuma had only been official US Territory since 1854, due to its inclusion in the Gadsden Purchase.

Prior to that, it was a US military outpost on Mexican territory. History supposes Mexico (i.e. Santa Anna) sold it to the US in order to get something, rather than get nothing, if it was lost via war.] Their goal was military in nature: to determine whether the river could carry supplies from the Gulf of California to military outposts in the Utah Territory. If that was possible, then the route would eventually be opened up to commercial enterprise, using the access granted by the Guadalupe-Hidalgo Treaty.

Ives was able to navigate the Colorado in the Explorer as far as (what was then called) Black Canyon, and from there Ives and two other crew members continued, rowing upstream into the deepening gorge, against the Colorado’s stiff current, portaging rapid after rapid. They were able to go another 30 miles upriver before they were forced to abandon their river journey. Continuing on foot, his overland journey took him down into the canyon at Diamond Creek, today part of the Hualapai Indian Reservation. This made him the first European American to reach the “Grand Canyon”.

In his 400+ page report, entitled “Report upon the Colorado River of the West, explored in 1857 and 1858 by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives, Army Corps of Topographical Engineers” (available for free download via Google), he makes clear his evaluation of the region:

“The region is, of course, altogether valueless. It can be approached only from the south, and after entering it there is nothing to do but leave. Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado river, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.”

[Fun facts: After this expedition, Ives next served as engineer and architect for the Washington National Monument from 1859 to 1860. During the American Civil War he joined the Confederate Army and served in several engineering capacities, and was finally appointed aide-de-camp to President Jefferson Davis from 1863 to 1865. After the war he settled in New York City where he died November 12, 1868.]

The most commonly-known American explorer of the Grand Canyon was John Wesley Powell, the second-ever director (1881-94) of the US Geological Survey (USGS) and one of the founders of the National Geographic Society (1888).

Powell was born in Mount Morris, New York, to a family that moved westward several times during his childhood, setting him up for a career in adventuring.  His youth reads like a Davy Crockett / Daniel Boone type of mythology, especially concerning “in 1856, when but 22 years old, he descended the Mississippi alone in a rowboat from the Falls of St. Anthony to its mouth, making collections on the way.” During the Civil War, he joined the 20th Illinois Volunteers as a cartographer, topographer and military engineer; his education got him commissioned him as a Second Lieutenant, and he was soon promoted to Captain of an artillery company. At the Battle of Shiloh in April 1962, he lost most of his right arm to a minie ball shot; the effects of the battlefield amputation left him with raw nerve endings in the stump which affected him for the remainder of his life. Despite the injury, he returned before the end of the War and saw command in positions at Vicksburg, Atlanta & Nashville. Promoted to Major before Atlanta, he ended the war a brevet Lieutenant Colonel (an award made for gallantry or meritorious service, rather than for command); in retirement, he preferred to be called “Major”.

His youth reads like a Davy Crockett / Daniel Boone type of mythology, especially concerning “in 1856, when but 22 years old, he descended the Mississippi alone in a rowboat from the Falls of St. Anthony to its mouth, making collections on the way.” During the Civil War, he joined the 20th Illinois Volunteers as a cartographer, topographer and military engineer; his education got him commissioned him as a Second Lieutenant, and he was soon promoted to Captain of an artillery company. At the Battle of Shiloh in April 1962, he lost most of his right arm to a minie ball shot; the effects of the battlefield amputation left him with raw nerve endings in the stump which affected him for the remainder of his life. Despite the injury, he returned before the end of the War and saw command in positions at Vicksburg, Atlanta & Nashville. Promoted to Major before Atlanta, he ended the war a brevet Lieutenant Colonel (an award made for gallantry or meritorious service, rather than for command); in retirement, he preferred to be called “Major”.

After the war, he returned to the field of academics, with an emphasis on exploring the American West. Working with colleagues at the Smithsonian Institution, in 1867 he mounted an expedition to explore the mountains of the Colorado Territory and record their geography. Using his connections to former commander (& now US President) Ulysses S. Grant, he was able to purchase rations at military commissaries along his exploration route, aiding his journey by helping keep costs low. A second journey in 1868 led him to craft a strategy to plan exploring the last great ’empty’ region of the American West – the Colorado River system.

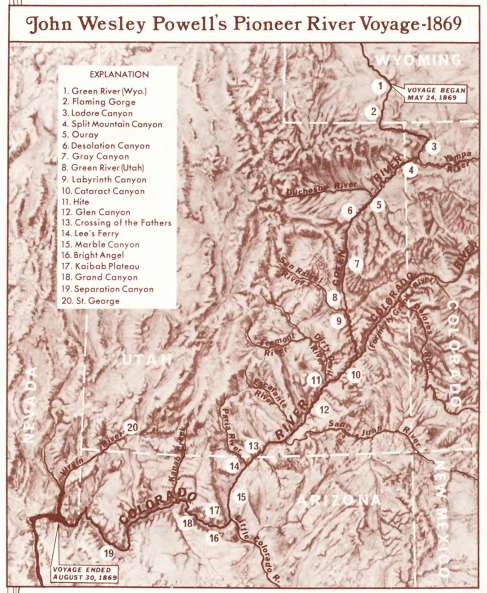

During the winter of 1868-9, he resided in northwestern Colorado and planned out his route. His plan was to start from one of the most northern reaches of the system, the Green River in Wyoming.

From there, he would traverse south along the river to its supposed junction with the Colorado, and then they would make their way through the “Great Unknown” until they got to the Mormon settlement of St. Thomas at the mouth of the Virgin River at the western end of the Canyon (currently under Lake Mead), which they knew was part of the Colorado River system thanks to the Ives expedition. The goal was to spend up to 10 months travelling & surveying the Green & Colorado Rivers right up to the mouth of the Virgin River.

On May 4, 1869, at the age of 35, with four boats and eleven men, armed with “two sextants, four chronometers, a number of barometers, thermometers, compasses, and other instruments,” Powell set off on what would become one of his most famous expeditions: the exploration of the Colorado River. The expedition was to enter into that “Great Unknown,” take scientific measurements, chart the region, and effectively complete the nation’s maps – the Grand Canyon was still considered “unexplored territory” on most US maps.

armed with “two sextants, four chronometers, a number of barometers, thermometers, compasses, and other instruments,” Powell set off on what would become one of his most famous expeditions: the exploration of the Colorado River. The expedition was to enter into that “Great Unknown,” take scientific measurements, chart the region, and effectively complete the nation’s maps – the Grand Canyon was still considered “unexplored territory” on most US maps.

From the outset, difficulties emerged that threatened to derail the journey, or simply leave them dead. The route carried them from Wyoming into eastern Utah, where the Green River met the Grand River, and the confluence formed the Colorado River. (“Colorado” is Spanish for “red river” because when it rained the side tributaries spilled their muddy sediment into the clear green waters of the main channel, causing it to run red and thick with silt.) They lost one boat, and its supplies, a month into the trip, which led an Englishman named Frank Goodman to abandon the journey. [Fun fact: Goodman was able to walk to a nearby settlement and lived out his life hunting, trapping on and near the Ute Reservation, and later raising a family in Vernal, Utah.] They had to portage past many unmapped rapids, occasionally having to scale canyon walls to avoid particularly treacherous portions. On August 28, three more men abandoned the journey after losing their boat to a patch of rapids, believing they wouldn’t survive to the end of the route. The three men – O.G. Howland, his brother Seneca, and Bill Dunn – hiked out of the Canyon & headed for any form of civilization they could find, only to be killed by a band of Shivwits Paiute Indians who were looking for miners that had killed a member of a neighbouring tribe.

Two days after the three men left the team, Powell & the remaining five members of the expedition reached the Virgin River on Aug. 30, 1869.

(source)

(source)

Their planned 900-mile, 10-month journey had taken only 99 days. They lost two boats & four men, and a good portion of the equipment they had brought along and records they had tried to keep. Their only remaining supplies were a few pounds of moldy flour. They also took no photographs, because the conditions were so difficult and the route unknown; it was enough to have survived relatively unscathed.

This lack of photographic & scientific documentation led Powell to plan a second expedition for 1871-72, which he tied into a US government desire to survey the Colorado & Green River watersheds, for the purposes of opening up new territory for homesteading. On July 12, 1870, Congress appropriated $12,000 for Powell to survey the lands adjoining the Colorado River and its tributaries. The Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, later known as the Powell Survey, was the third of the major western scientific surveys. On May 22, 1871, Powell’s second Canyon expedition departed from Green River, Wyoming.

After wintering in Kanab, Utah, the expedition resumed its course and entered the Grand Canyon at Lee’s Ferry on August 17, 1872.

Powell’s boat, moored at Marble Canyon. He had the chair affixed so he could see over the crew & scout river conditions.

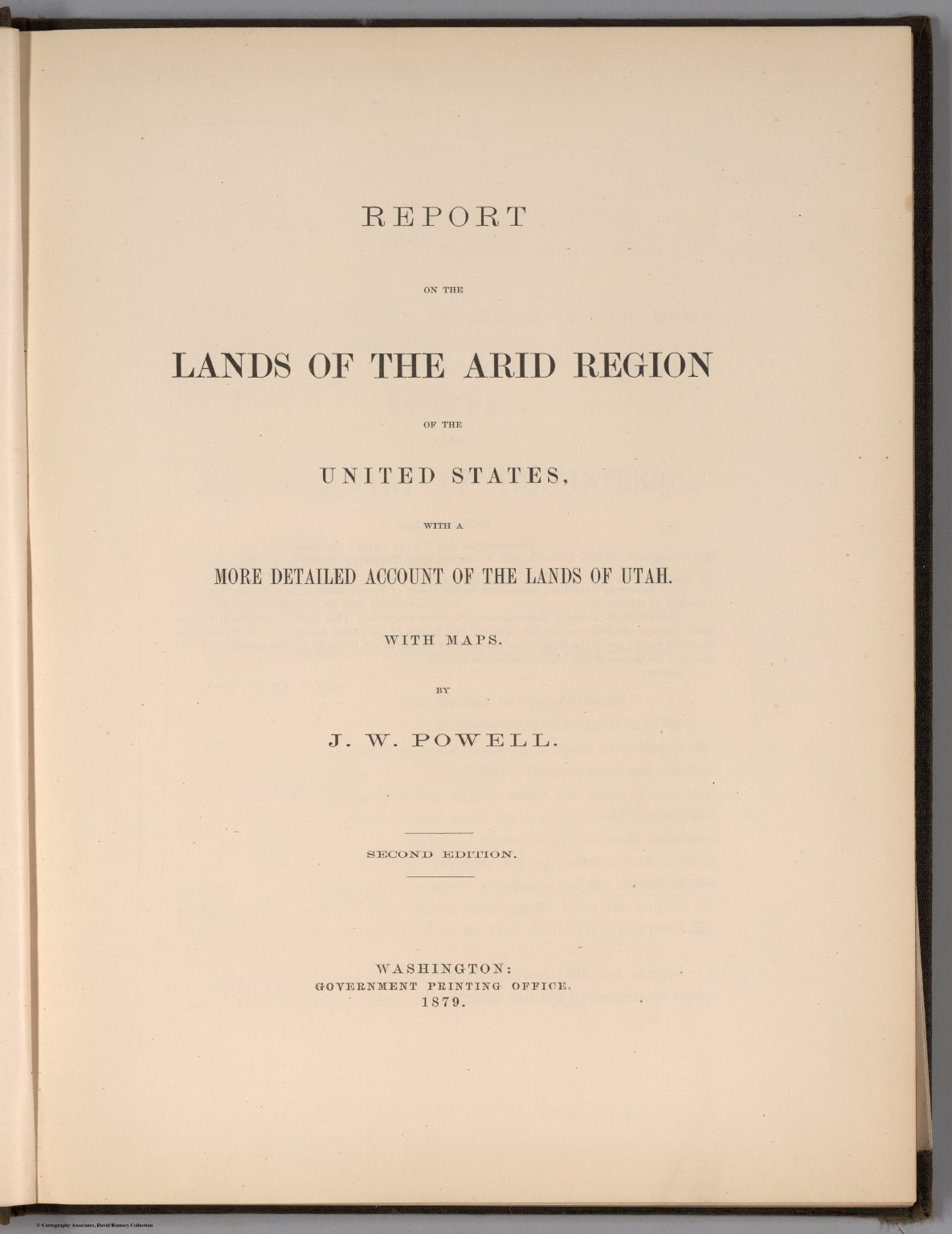

This journey, and the accompanying surveys of the Colorado & Great Plains basins, culminated eight years of work and led to the publication in April 1878 of Powell’s seminal work, “Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, With a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah”.

This report outlined what Powell considered to be a sensible settlement policy for the Great Plains & Colorado basin, given the scarcity of available water supplies. He produced a map outlining various drainage basins, and noted that settlement & farming should be predicated upon tenant accessibility to water, and that agriculture should be limited to areas of sustainable water supplies. Powell argued that settlement should be gradual and restricted, and that the government – not private individuals or agricultural enterprises – should control water rights, in order to ensure viable supplies for the farming population. In 1888, in his role as Director of the USGS, he received funding for an irrigation mapping project of the west, from which recommendations for future settlement would be derived. He advocated for limits, based on available water supplies; establishing “irrigation districts” wherein landowners would share & develop the resource withing their regions; and an end to the grid system of establishing homesteads – preferring instead that plots be aligned to natural waterways & drainages. (See map above)

[Fun facts: Politicians ignored Powell’s recommendations, instead choosing to promote homesteading and end funding for his mapping projects. Instead of Powell’s measured science, the politicians based their decisions on the popular science of Professor Cyrus Thomas. Thomas suggested that agricultural development of land would change climate and cause higher amounts of precipitations, claiming that “rain follows the plow“. As people pushed west in ever-increasing numbers, some of them, at least, carried along a persistent vision of unlimited prosperity and growth – the belief that agricultural development of “The Great American Desert” would result in increased precipitation, thus perpetuating the agricultural settlements that had been established.

By going with the science that would keep them in office, the politicians allowed a future economic disaster to gain traction. Powell understood that unbridled optimism and headlong land development would lead to environmental ruin and mass human suffering. Rapid settlement of the Great Plains via the Homestead Act (1862), which allowed individuals over the age of 21 to stake a claim for parcel of land of 160 acres (no matter the accessibility to water), combined with exhaustion of natural aquifers and over-irrigation, helped contribute to the “Dust Bowl” conditions of the 1930s. The great Dust Bowl would displace some 2.5 million Americans and set off one of the greatest migrations in U.S. history. This led to population upheaval, as thousands of farms were abandoned or went bankrupt, which changed internal US migration patterns from rural to urban, and began the concentration of populations in major centres due to the relative availability of employment & government services.

The decline of the American Great Plains farmer has its origins in the 1878 report of John Wesley Powell.]

Fed up with the bureaucratic politics, he resigned from the USGS in 1894. He retained his position at the Bureau of Ethnology (part of the Smithsonian), and used his retirement to continue to collect & collate material on the Indian tribes of the west & southwest. He retreated into his study of anthropology, hoping to leave more than just an academic legacy. He himself considered the two great works of his life to be the sympathetic study of the American Indian, and the attempt to establish an ecologically sound dryland democracy in the West.

Powell died in September 1902. Due to his rank and national import, plus status as a Civil War veteran, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery,

and his wife was buried alongside him in 1924. In 1912 a memorial was erected to him on the south rim of the Canyon, at a place now called Powell Point. It commemorates Powell’s two expeditions through the Canyon, and names those who finished the journey with him – purposely leaving off those who abandoned the treks part-way through.

2019 marks the sesquicentennial of Powell’s epic 1869 Expedition down the Green and Colorado rivers, so I figured I’d add extra material about him to this piece about the Grand Canyon. Some well-intentioned but likely highly-underprepared Arts majors are going to try and replicate a portion of the adventure this summer.

The reports of his two expeditions made Powell a folk hero, and brought attention to the need to protect the area from being disturbed by the westward expansion of the Manifest Destiny. The first bill to establish Grand Canyon National Park was introduced in 1882 by then-Senator Benjamin Harrison, which would have established Grand Canyon as the third national park in the United States, after Yellowstone and Mackinac. That bill was defeated, and attempts to reintroduce the motion in 1883 & 1886 both failed. However, upon his election to the presidency in 1892, in 1893 Harrison used an Executive Order to establish the Grand Canyon Forest Reserve, offering federal protection for both the canyon rim areas as well as the valley floor (because Arizona was still a Territory).

Teddy Roosevelt visited the Canyon in 1903, and was so moved that in 1906 he used the recently signed Antiquities Act to have it declared the Grand Canyon Game Reserve, and in 1908 he made it a national monument. His famous words on the Canyon echo his belief in protecting such vistas as part of America’s natural heritage:

“Leave it as it is. You cannot improve it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you do is to keep it for your children, your children’s children, and for all who come after you, as the one great sight which every American . . . should see.”

Senate bills to establish a national park were introduced and defeated in 1910 and 1911. Lingering opposition, in the form of private business & mining interests, delayed adoption of National Park status. But the introduction of a federal National Park Service to provide oversight & management, and the inability of the park’s opponents to prove a viable for-profit option existed, made the inevitability of the Canyon’s elevation almost a foregone conclusion.

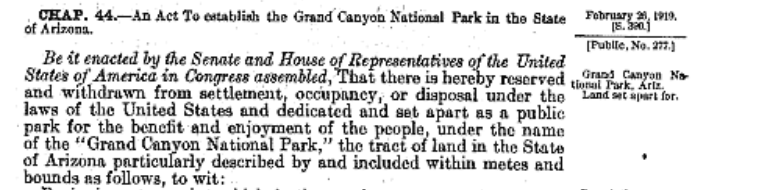

Senator Henry Ashurst of Arizona, whose father had once prospected the canyon’s depths, introduced Senate Bill 390 on April 4, 1917. The legislation quickly passed the Senate, but the United States’ entry into World War I, details concerning the rights of private interests, and other matters of continuing commercial use delayed approval by the House Committee on Public Lands until October 1918.

The Grand Canyon National Park Act

was finally signed by President Woodrow Wilson on February 26, 1919. The Act established the park boundaries of the Grand Canyon, protected the Grand Canyon from non-permitted mineral exploitation, irrigation projects and construction, and maintained the Havasupai Indians’ right to use the land.

One tiny bit of bureaucratic geographical housekeeping occurred in 1921. In practice, the “Colorado River” only existed once the Grand & Green Rivers met in Utah.

In February 1921, Congressman Edward Taylor of Colorado spoke to a meeting of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce on the topic of changing the name of the Grand River to the Colorado, extending the name of the river from the confluence up to its headwaters in Grand County, Colorado. Opposition was received from the Utah & Wyoming delegations, because the Green is the longer of the two Colorado tributaries and geographical convention dictated that that is what determines a river’s name. However, Taylor (successfully) argued before the Committee that the Grand contributes more water volume to the Colorado, and that should be the determining factor. Taylor’s House Joint Resolution 460 was passed by the House and Senate on July 25, 1921, and the bill signed into law by President Harding proclaimed the stretch of river that runs from its source in Grand County to the confluence with the Green would be known as the upper stream of the Colorado.

(source)

The National Park Service, established as an agency of the Department of the Interior via the “National Park Service Organic Act” in 1916, assumed administration of the park – the 14th National Park in the USA (to that time). [Find a timeline of National Parks establishment here.] In 1919, just over 44,000 people visited the Canyon; in 2018, 6.3 million people visited the Grand Canyon. A National Park Service report shows that more than 6.2 million recreational visitors to Grand Canyon National Park in 2017 spent $667 million in communities near the park. That spending supported 9.423 jobs in the local area and had a cumulative benefit to the local economy of $938 million.

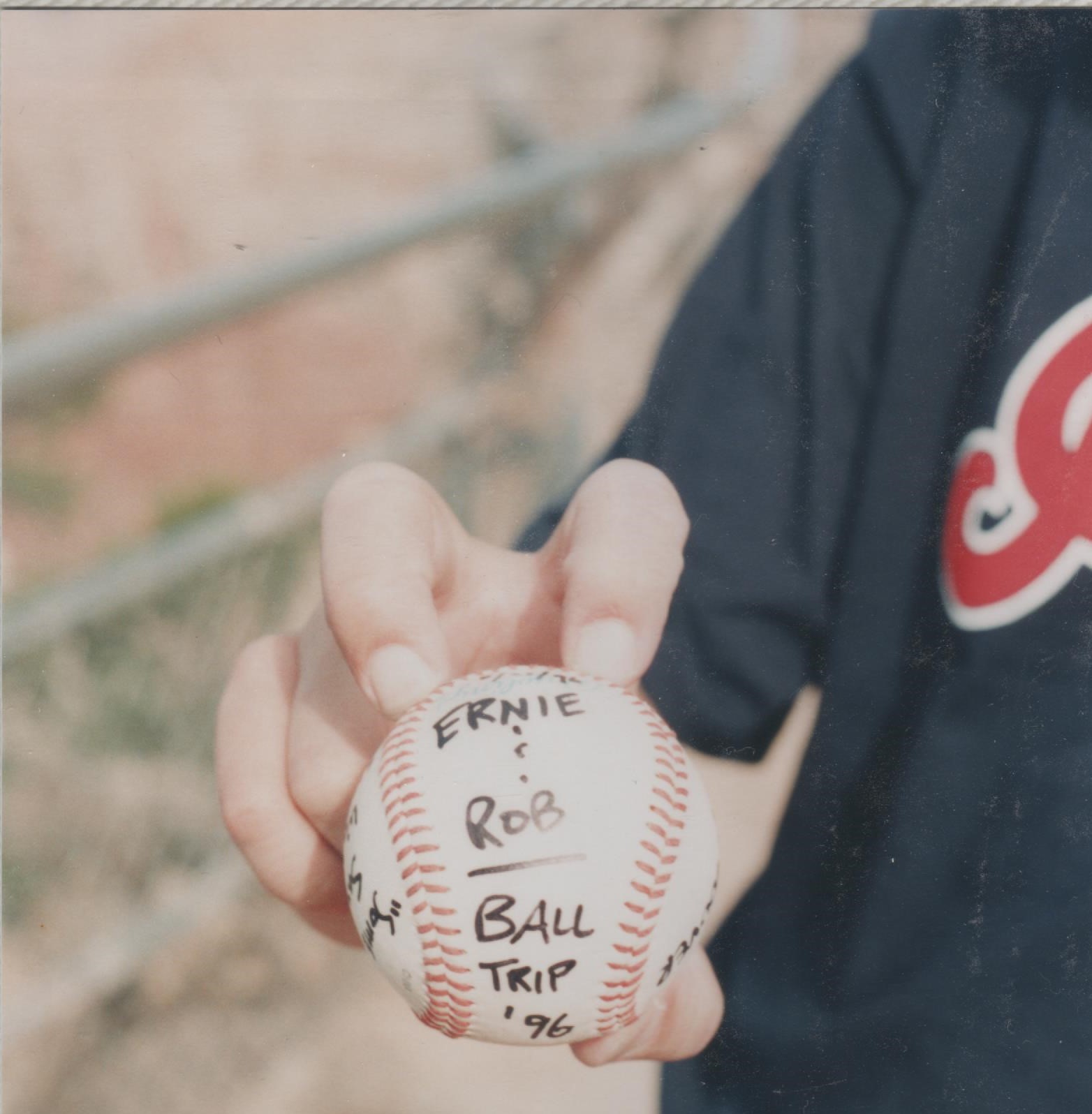

I’ve been to the Grand Canyon once. I was on a baseball road trip with a friend, and after spending a couple of days in Phoenix we decided to head up through the Canyon area on our way to Las Vegas. I’ve got to say, even spending just six hours there was pretty cool.

They say you should take only photos and leave only memories. Well, I left a little more than that.

Hopefully, I didn’t kill somebody.

All of the sources I used are highlighted throughout the piece. It’s way too many to list here at the end. Unless noted, all maps come from Wikipedia.

I didn’t figure anyone needed more reading about the Grand Canyon. That stuff is readily available online or in old travel brochures at your grandparents house in the trunk marked “vacation photos”.

But I did learn a bunch about the explorers, which was quite cool. Given it’s the sesquicentennial of his 1869 journey, here’s further reading on or by John Wesley Powell, if you’re so inclined:

- John Wesley Powell – Soldier, Explorer, Scientist. USGS. (1969)

- Stenger, W. Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West. Penguin. (1964) Via Googlebooks.

- Powell, J.W., Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, With a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah. US Printing Office. (1878) Via biodiversitylibrary.org.

- Hein, R. John Wesley Powell: Explorer, Thinker, Scientist and Bureaucrat. Via Wyoming State Historical Society. (December 2018)

- Jenkins, M.C., John Wesley Powell: Soldier, Explorer, Scientist and National Geographic Founder. Via National Geographic. (January 2018)

[…] the thirty year conflict in Vietnam finally came to an end. Without turning this into a full on [DFO] History Corner, I’ll keep the history lesson brief before moving on to the recipe for the Saigon […]

Great read, but what about the radiation?!?

For enjoyment, you can look up the Grand Canyon on Yelp and see people give it three stars (dock 1-star because so far from their Vegas Strip hotel; dock 1-star because “standing at the rim, it’s too big to comprehend the size.”).

“Profitless locality” sounds like a burn from “I love the 80s”. Great stuff.

Why didn’t they just drive there in a Canyonero?

Ya!

Unexplained fires are a matter for the courts.

Really? That’s crazy.

Excellent work. Inspiring enough that I am going to visit this year after reading this.

I’ve never been and now that seems like a goddamn tragedy since I’m in California. I’ve also driven just a few miles south of the canon on route 40, formerly Route 66.

I know. No fucking excuses.

You gotta remedy that. Don’t get lost like Bobby and Cindy Brady though. If I remember the episode correctly, I think they were kidnapped and molested by Sam the butcher.

I’ve said it before and i’ll say it again: I LOVE when you get historical!

Fun fact: I’ve done the hike down the Canyon where you end up at a Havasupai village.

Yes, I took the helicopter back up.

You’re allowed in Arizona?

Only if travels with an Anglo.

I look white. Don’t tell anyone.

Look, I’m not saying Arizona is the worst state in the Union (I am), but their best attraction is literally a big hole in the ground.

Yeah, but so’s New York’s

Best things about Arizona:

1) Grand Canyon

2) Spring Training

3) ASU Coeds/Mill Street Bars

.

.

.

.

3,682,913) Getting stung by a scorpion while being bitten by a rattlesnake

3,683,914) Joe Arpaio

4) “Stumbling upon” FTV Girls doing their public scenes around Tempe.

5) Maybe running into Wifey around Scottsdale.

And still…Arizona’s a damn sight better than Alabama.

Great read, alemanbobby! It’s truly an incredible place, where the first impression is something like “This cannot be real.” Need to plan a trip soon.

I’d like to visit, but …

That’s the most entertaining Cardinals season preview I’ve ever read.

JK, good stuff.